It has long been recognized that the early-twentieth-century philosopher Henri Bergson placed particular emphasis on a 'vitalist' interpretation of biology. Many of his critics, including George Santanaya, Julian Huxley, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, identified Bergson's appeal to an 'élan vital' (most prominently made in his 1907 Creative Evolution) with a problematically unscientific or mystical attitude towards the world. Similarly thinkers who looked to draw on Bergson's work during the twentieth century, including Georges Canguilhem and Gilles Deleuze, also sought to rehabilitate or re-consider the status of 'vitalism' along with it.

Instead of taking one or another side in this ongoing debate, this short essay highlights the extent to which Bergson's vitalist beliefs were historically plausible. That is, it examines ways in which Bergson drew on a tradition of research into the nature of life that had become increasingly prominent during the final decades of the twentieth century. It suggests that in aligning himself with the vitalist tradition of biology as it manifested itself in 1907, Bergson was not investing in a discredited approach: on the contrary, though he was careful to avoid making his philosophy rely on the conclusions of vitalist science, he found in it a form of legitimation that was as persuasive to early twentieth century scientists as it was to philosophers. Nevertheless, as will be seen, the seeming confirmation of Bergson's philosophy in the science of life proved short-lived. During the 1920s and 1930s, Bergson's evocation of vitalism would be re-interpreted as a sign of scientific weakness rather than scientific strength.

By the time that Creative Evolution was published, Bergson had come increasingly to rely on a particular strand of scientific thinking that (he believed) accorded particularly well with his philosophy. His 1896 book Matter and Memory had introduced a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry. In Creative Evolution, however, Bergson appeared wiling to go further: biological science was to be brought back within the purview of the philosophical tradition from which (Bergson believed) it had originated. This was to be achieved, he argued, through the constitution of a theory of knowledge that, because based in immediate experience, would also be a theory of life.

'Together', Creative Evolution contended, philosophy and vital science would 'solve by a method more sure, brought nearer to experience, the great problems that philosophy poses.' By thinking together a set of contentions regarding the originary nature of life with his own introspectively-derived conclusions regarding the nature of memory and experience, it would be possible to arrive at a situation in which biological and indeed all science would appear merely as 'psychics inverted'. Ultimately, living matter for Bergson evinced a psychological process which was 'in its essence... an effort to accumulate energy and then to let it flow into flexible channels, changeable in shape, at the end of which it will accomplish infinitely varied kinds of work.' Philosophical practice similarly consisted in a process of accumulation and dissimilation, but of conscious awareness. Experience alternated between an intellectual state in which the 'whole personality concentrate[d] itself', and a dream-like, 'scattered', 'intuitive' state in which the originary nature of matter became perceptible. The vital mind thus 'used' space 'like a net with meshes that can be made and unmade at will, which thrown over matter, divides it as the needs of our action demand.' The life sciences, properly interpreted, constituted an introspective investigation of the processes of extension and retraction as they manifested themselves in the living substance.

Recent historiography on relations between psychology and life science in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century suggests that the hope that Bergson held out for the latter was by no means misplaced. For example, Judy Schloegel and Henning Schmidgen point to the prominence during the final decades of the nineteenth century of a physiological tradition in which the origins of psychological existence were associated with that of the most simple known forms of organic matter; in the work of Ernst Haeckel, Max Verworn, and Alfred Binet, psychological properties such as sensation, volition and intention were discovered in apparently primordial forms of life, most notably the cell. Though these investigators differed regarding the extent to which they regarded such properties as inhering in protoplasmic or nucleic parts of cells, all agreed that each could be considered an independent psychic unit. Human psychology was the manifestation of the simultaneous action of the countless autonomously-acting individuals that composed their bodies: properly understood, mind was indeed able to dissimilate into its originary nature.

One of the most pressing questions facing those who adhered to such conceptions was that of exactly how independently-acting cellular individuals could combine to form more complex psychological wholes. Different tendencies existed within the conceptual framework of cellular individuality. One contention that gained considerable traction during the final years of the nineteenth century was the so-called 'amoeboid' theory of cellular interaction. Just as individual cells could be identified as manifesting vital capacities such as autonomous extension and contraction, each nerve-cell or 'neuron' was, in the conception of histologists such as Mathias-Marie Duval, an independently-acting contributor to the neurological whole. Ramón y Cajal suggested in a study of 1890 that nerve fibres could be seen to grow outwards from their cellular origins. Though Cajal would later renounce this view, he and like-minded theorists believed that this constituted evidence that nerve cells behaved just like amoeba in that they expanded, contracted, and moved their extremities from place to place. The possibility of psychological variation was thereby assured: by altering the proximity of each cell to one another, amoeboid movement altered the extent to which electrical nerve-impulses could be communicated. The psychologically-individual cells of the nervous system combined to create a greater whole.

Contrasting with this conception of cellular activity was an alternative, 'network'-centred vision of neurological connection. Though the notion that the body was permeated by a fibrous network of nerves through which organs communicated had been prominent in physiology prior to the nineteenth century, this had been sidelined as the cell theory had been established. In 1869 however, Thomas Henry Huxley had prominently declared protoplasm the 'physical basis of life'. First propounded by Max Schultze in 1860, it had been Haeckel who presented the most influential discussion of its relevance to psychology. As Robert Brain notes, Haeckel's contention that that protoplasm 'had the ability to receive and maintain the waveform vibrations of the external world' and thereby pass on organic characteristics from one generation to the next achieved great prominence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Haeckel further argued that a protoplasmic capacity for the reception and storage of wave-forms endowed cells with psychological capacity. Well into the twentieth century, histologists such as Camillo Golgi, Hans Held, Stephan Apáthy and Albrecht Bethe presented evidence that nerves could link together via continuously connecting organic structures. A significant strand of late-nineteenth-century physiological psychology thereby identified the variability of nervous excitation not with the properties of individual cells as such, but with the vital and extensible properties of the protoplasm that (it was held) was common to them all.

Adherents of cellularly-distinct conceptions of neuronal connection portrayed them as confirming associationist contentions regarding the nature of psychology. For example, US physician Francis Xavier Dercum argued that the 'amoeboid' expansion and retraction of individual cells underlay variously: hysteria; hypnotic and dream states; sleep; and trains of thought themselves. These latter, Dercum contended, appeared 'to follow purely mechanical lines' of association and disassociation between the sense impressions that they carried. In 1898, Boris Sidis and Ira van Gieson separately elaborated this thesis to account for states of sanity and insanity: in Gieson's words, 'unsoundness of mind' was caused by the 'dissociation' of the 'higher and last evolved parts of the brain, in the presence of pathogenic stimuli.' For amoeboid theorists, the apparent mechanical capacity of nerve cells to alter their proximity to one another presented physical confirmation of the existence of psychological associations.

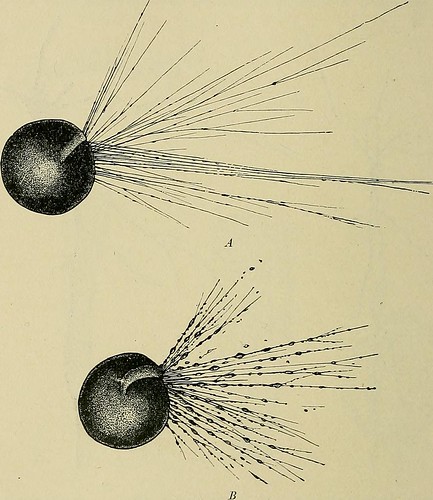

In a similar way, adherents of the protoplasmic conception of neuronal connection identified mental activity with the presumed properties of this vital substance. Especially prominent amongst such adherents was the renowned physiologist Ewald Hering. Calling for physiologists to 'cease considering physiology merely as a sort of applied physics and chemistry,' Hering argued that the causes of nervous action were to be found in two independent and contradictory tendencies of protoplasmic matter. On the one hand, a tendency towards 'assimilation' could be perceived within living substance. This was balanced by an equal and opposite tendency, that towards 'dissimilation'. Where assimilation predominated, organic matter increased in activity. Where dissimilation predominated, activity decreased. There were thus 'two closely interwoven processes, which constitute the metabolism (unknown to us in its intrinsic nature) of the living substance'. The variable energetic states of protoplasm expressed itself in the nervous system as the throwing-out of countless connections between cellular bodies: 'a nerve-trunk is... a bundle of living arms which the elementary organisms of the nervous system send forth for the purpose of entering into functional connexion with one another, or of permitting the phenomena of the outside world to act upon them, or of exercising control over other organs' (see Fig. 1). As Michael Foster put it for the 1902 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 'in Hering's conception the mere condition of the protoplasm, whether it is largely built up or largely broken down, produces effects which result in a particular state of consciousness.' Sensation was not so much the consequence of impressions on sensory organs that were then conveyed to the mind via the nerves, as the establishment of sympathetic rhythms between the various realms of existence. Thus in the case of visual sensations, Hering argued that protoplasm vibrated according to the frequency of light-waves connecting with the retina. Brain recounts how at the Paris Societé de biologie, Binet and others developed similar explanatory schema to account variously for hypnotic and hysteric states, sleep, aesthetic experience, and even paranormal phenomena. Protoplasm spread both inwards and outwards from the vital mind, bringing mental life into vibratory harmony with that with which it connected.

By insisting on the active, temporally extensive nature of both bodily and psychological existence, Bergson's appeal to organic sciences was thereby aligned with a highly active research tradition within physiological science. For him, such studies as those detailed above indicated that 'life is a movement, materiality is the inverse movement, and each of these two movements is simple, the matter which forms a world being an undivided flux.' Here then was confirmation of the philosophical import of physiological investigation. To the extent that physiology confirmed the evidence of introspective insight, it presented a means by which the philosopher might demonstrate the organically creative presence of thought within the body.

Bergson's appeal to an 'élan vital' was not then an isolated or even a scientifically unrealistic claim for a philosopher to make during the early years of the nineteenth century. In identifying his thought with this scientific trend, Bergson was in many respects foreshadowing twentieth-century Western philosophers' increasing reliance on scientifically-derived conclusions (generally associated with opponents of his such as Huxley and Bertrand Russell). Nevertheless, though we should acknowledge the scientific plausibility of Bergson's thinking in 1907, it should also be noted that Bergson continued to adhere to his vitalist conclusions even as the contentions to which they appealed fell out of biological fashion. By the 1930s, it had become increasingly common to refer to Bergson as an unscientific 'mystic', and Bergson himself did little to dispel this impression. If there is a lesson here for the scientifically inspired philosophers of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries then, it might be this: those who live by the (scientific) sword, die by the (scientific) sword. Or, less combatively: if you rely on science to legitimate your philosophy, be ready to alter your conclusions when scientific thinking changes.

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cites

B. Sidis, The Psychology of Suggestion: A Research into the Subconscious Nature of Man and Society (1898).

B. Sidis, The Psychology of Suggestion: A Research into the Subconscious Nature of Man and Society (1898).

Description:'Adherents of cellularly-distinct conceptions of neuronal connection portrayed them as confirming associationist contentions regarding the nature of psychology... In 1898, Boris Sidis and Ira van Gieson separately elaborated this thesis to account for states of sanity and insanity.'

-

Cites

E. Clarke and L.S. Jacyna, Nineteenth-Century Origins of Neuroscientific Concepts (Berkeley, CA., Los Angeles, CA. and London: University of California Press, 1987).

E. Clarke and L.S. Jacyna, Nineteenth-Century Origins of Neuroscientific Concepts (Berkeley, CA., Los Angeles, CA. and London: University of California Press, 1987).

Description:'by altering the proximity of each cell to one another, amoeboid movement altered the extent to which electrical nerve-impulses could be communicated. The psychologically-individual cells of the nervous system combined to create a greater whole.

Contrasting with this conception of cellular activity was an alternative, 'network'-centred vision of neurological connection. Though the notion that the body was permeated by a fibrous network of nerves through which organs communicated had been prominent in physiology prior to the nineteenth century, this had been sidelined as the cell theory had been established. In 1869 however, Thomas Henry Huxley had prominently declared protoplasm the 'physical basis of life'.'

-

Cites

J.J. Schloegel and H. Schmidgen, 'General Physiology, Experimental Psychology, and Evolutionism: Unicellular Organisms as Objects of Psychophysiological Research, 1877-1918', Isis 93 (4) (2002), pp. 614-645.

J.J. Schloegel and H. Schmidgen, 'General Physiology, Experimental Psychology, and Evolutionism: Unicellular Organisms as Objects of Psychophysiological Research, 1877-1918', Isis 93 (4) (2002), pp. 614-645.

Description:'Recent historiography on relations between psychology and life science in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century suggests that the hope that Bergson held out for the latter was by no means misplaced. For example, Judy Schloegel and Henning Schmidgen point to the prominence during the final decades of the nineteenth century of a physiological tradition in which the origins of psychological existence were associated with that of the most simple known forms of organic matter; in the work of Ernst Haeckel, Max Verworn, and Alfred Binet, psychological properties such as sensation, volition and intention were discovered in apparently primordial forms of life, most notably the cell.'

-

Cites

L. Otis, Networking: Communicating with Bodies and Machines in the Nineteenth Century (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001).

L. Otis, Networking: Communicating with Bodies and Machines in the Nineteenth Century (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001).

Description:'by altering the proximity of each cell to one another, amoeboid movement altered the extent to which electrical nerve-impulses could be communicated. The psychologically-individual cells of the nervous system combined to create a greater whole.

Contrasting with this conception of cellular activity was an alternative, 'network'-centred vision of neurological connection. Though the notion that the body was permeated by a fibrous network of nerves through which organs communicated had been prominent in physiology prior to the nineteenth century, this had been sidelined as the cell theory had been established. In 1869 however, Thomas Henry Huxley had prominently declared protoplasm the 'physical basis of life'. First propounded by Max Schultze in 1860, it had been Haeckel who presented the most influential discussion of its relevance to psychology. As Robert Brain notes, Haeckel's contention that that protoplasm 'had the ability to receive and maintain the waveform vibrations of the external world' and thereby pass on organic characteristics from one generation to the next achieved great prominence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.'

-

Cites

O. Breidbach, 'The Controversy over Stain Technologies - an Experimental Reexamination of the Dispute on the Cellular Nature of the Nervous System around 1900', History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 18 (2) (1996), pp. 195-212.

O. Breidbach, 'The Controversy over Stain Technologies - an Experimental Reexamination of the Dispute on the Cellular Nature of the Nervous System around 1900', History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 18 (2) (1996), pp. 195-212.

Description:'As Robert Brain notes, Haeckel's contention that that protoplasm 'had the ability to receive and maintain the waveform vibrations of the external world' and thereby pass on organic characteristics from one generation to the next achieved great prominence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Haeckel further argued that a protoplasmic capacity for the reception and storage of wave-forms endowed cells with psychological capacity. Well into the twentieth century, histologists such as Camillo Golgi, Hans Held, Stephan Apáthy and Albrecht Bethe presented evidence that nerves could link together via continuously connecting organic structures.'

-

Cites

R. Brain, 'Protoplasmania', in B. Larson and F. Brauer (eds.), The Art of Evolution: Darwin, Darwinisms, and Visual Culture (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2009), pp. 92-123.

R. Brain, 'Protoplasmania', in B. Larson and F. Brauer (eds.), The Art of Evolution: Darwin, Darwinisms, and Visual Culture (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2009), pp. 92-123.

Description:'Though the notion that the body was permeated by a fibrous network of nerves through which organs communicated had been prominent in physiology prior to the nineteenth century, this had been sidelined as the cell theory had been established. In 1869 however, Thomas Henry Huxley had prominently declared protoplasm the 'physical basis of life'. First propounded by Max Schultze in 1860, it had been Haeckel who presented the most influential discussion of its relevance to psychology. As Robert Brain notes, Haeckel's contention that that protoplasm 'had the ability to receive and maintain the waveform vibrations of the external world' and thereby pass on organic characteristics from one generation to the next achieved great prominence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Haeckel further argued that a protoplasmic capacity for the reception and storage of wave-forms endowed cells with psychological capacity.'

-

Cites

R.M. Brain, 'Materialising the Medium: Ectoplasm and the Quest for Supra-Normal Biology in Fin-de-Siècle Science and Art', in A. Enns and S. Trower (eds.), Vibratory Modernism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), pp. 115-144.

R.M. Brain, 'Materialising the Medium: Ectoplasm and the Quest for Supra-Normal Biology in Fin-de-Siècle Science and Art', in A. Enns and S. Trower (eds.), Vibratory Modernism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), pp. 115-144.

Description:'Brain recounts how at the Paris Societé de biologie, Binet and others developed similar explanatory schema to account variously for hypnotic and hysteric states, sleep, aesthetic experience, and even paranormal phenomena. Protoplasm spread both inwards and outwards from the vital mind, bringing mental life into vibratory harmony with that with which it connected.'

-

Cites

S.E. Black, '"The Osler Medal Essay": Pseudopods and Synapses: The Amoeboid Theories of Neuronal Mobility and the Early Formation of the Synapse Concept', Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55 (1981), pp. 34-58.

S.E. Black, '"The Osler Medal Essay": Pseudopods and Synapses: The Amoeboid Theories of Neuronal Mobility and the Early Formation of the Synapse Concept', Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55 (1981), pp. 34-58.

Description:'Exactly how independently-acting cellular individuals could combine to form more complex psychological wholes [was uncertain around 1900]. Different tendencies existed within the conceptual framework of cellular individuality. One contention that gained considerable traction during the final years of the nineteenth century was the so-called 'amoeboid' theory of cellular interaction. Just as individual cells could be identified as manifesting vital capacities such as autonomous extension and contraction, each nerve-cell or 'neuron' was, in the conception of histologists such as Mathias-Marie Duval, an independently-acting contributor to the neurological whole. Ramón y Cajal suggested in a study of 1890 that nerve fibres could be seen to grow outwards from their cellular origins. Though Cajal would later renounce this view, he and like-minded theorists believed that this constituted evidence that nerve cells behaved just like amoeba in that they expanded, contracted, and moved their extremities from place to place.'

'Adherents of cellularly-distinct conceptions of neuronal connection portrayed them as confirming associationist contentions regarding the nature of psychology. For example, US physician Francis Xavier Dercum argued that the 'amoeboid' expansion and retraction of individual cells underlay variously: hysteria; hypnotic and dream states; sleep; and trains of thought themselves. These latter, Dercum contended, appeared 'to follow purely mechanical lines' of association and disassociation between the sense impressions that they carried. In 1898, Boris Sidis and Ira van Gieson separately elaborated this thesis to account for states of sanity and insanity: in Gieson's words, 'unsoundness of mind' was caused by the 'dissociation' of the 'higher and last evolved parts of the brain, in the presence of pathogenic stimuli.' For amoeboid theorists, the apparent mechanical capacity of nerve cells to alter their proximity to one another presented physical confirmation of the existence of psychological associations.'

-

Quotes

E. Hering, 'On the Theory of Nerve Activity', The Monist 10 (2) (Jan. 1900), pp. 167-187.

E. Hering, 'On the Theory of Nerve Activity', The Monist 10 (2) (Jan. 1900), pp. 167-187.

Description:'For amoeboid theorists, the apparent mechanical capacity of nerve cells to alter their proximity to one another presented physical confirmation of the existence of psychological associations.

In a similar way, adherents of the protoplasmic conception of neuronal connection identified mental activity with the presumed properties of this vital substance. Especially prominent amongst such adherents was the renowned physiologist Ewald Hering. Calling for physiologists to 'cease considering physiology merely as a sort of applied physics and chemistry,' Hering argued that the causes of nervous action were to be found in two independent and contradictory tendencies of protoplasmic matter. On the one hand, a tendency towards 'assimilation' could be perceived within living substance. This was balanced by an equal and opposite tendency, that towards 'dissimilation'. Where assimilation predominated, organic matter increased in activity. Where dissimilation predominated, activity decreased. There were thus 'two closely interwoven processes, which constitute the metabolism (unknown to us in its intrinsic nature) of the living substance'. The variable energetic states of protoplasm expressed itself in the nervous system as the throwing-out of countless connections between cellular bodies: 'a nerve-trunk is... a bundle of living arms which the elementary organisms of the nervous system send forth for the purpose of entering into functional connexion with one another, or of permitting the phenomena of the outside world to act upon them, or of exercising control over other organs' (see Fig. 1)... Sensation was not so much the consequence of impressions on sensory organs that were then conveyed to the mind via the nerves, as the establishment of sympathetic rhythms between the various realms of existence. Thus in the case of visual sensations, Hering argued that protoplasm vibrated according to the frequency of light-waves connecting with the retina.'

-

Quotes

F.X. Dercum, 'The Functions of the Neuron', Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 23 (8) (1896), pp. 513-523.

F.X. Dercum, 'The Functions of the Neuron', Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 23 (8) (1896), pp. 513-523.

Description:'Adherents of cellularly-distinct conceptions of neuronal connection portrayed them as confirming associationist contentions regarding the nature of psychology. For example, US physician Francis Xavier Dercum argued that the 'amoeboid' expansion and retraction of individual cells underlay variously: hysteria; hypnotic and dream states; sleep; and trains of thought themselves. These latter, Dercum contended, appeared 'to follow purely mechanical lines' of association and disassociation between the sense impressions that they carried.'

-

Quotes

H. Bergson (trans. A. Mitchell), Creative Evolution (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1911).

H. Bergson (trans. A. Mitchell), Creative Evolution (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1911).

Description:'It has long been recognized that the early-twentieth-century philosopher Henri Bergson placed particular emphasis on a 'vitalist' interpretation of biology. Many of his critics, including George Santanaya, Julian Huxley, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, identified Bergson's appeal to an 'élan vital' (most prominently made in his 1907 Creative Evolution) with a problematically unscientific or mystical attitude towards the world...

By the time that Creative Evolution was published, Bergson had come increasingly to rely on a particular strand of scientific thinking that (he believed) accorded particularly well with his philosophy. His 1896 book Matter and Memory had introduced a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry. In Creative Evolution, however, Bergson appeared wiling to go further: biological science was to be brought back within the purview of the philosophical tradition from which (Bergson believed) it had originated. This was to be achieved, he argued, through the constitution of a theory of knowledge that, because based in immediate experience, would also be a theory of life.

'Together', Creative Evolution contended, philosophy and vital science would 'solve by a method more sure, brought nearer to experience, the great problems that philosophy poses.' By thinking together a set of contentions regarding the originary nature of life with his own introspectively-derived conclusions regarding the nature of memory and experience, it would be possible to arrive at a situation in which biological and indeed all science would appear merely as 'psychics inverted'. Ultimately, living matter for Bergson evinced a psychological process which was 'in its essence... an effort to accumulate energy and then to let it flow into flexible channels, changeable in shape, at the end of which it will accomplish infinitely varied kinds of work.' Philosophical practice similarly consisted in a process of accumulation and dissimilation, but of conscious awareness. Experience alternated between an intellectual state in which the 'whole personality concentrate[d] itself', and a dream-like, 'scattered', 'intuitive' state in which the originary nature of matter became perceptible. The vital mind thus 'used' space 'like a net with meshes that can be made and unmade at will, which thrown over matter, divides it as the needs of our action demand.' The life sciences, properly interpreted, constituted an introspective investigation of the processes of extension and retraction as they manifested themselves in the living substance.'

'though we should acknowledge the scientific plausibility of Bergson's thinking in 1907, it should also be noted that Bergson continued to adhere to his vitalist conclusions even as the contentions to which they appealed fell out of biological fashion.'

-

Quotes

![H. Bergson (trans. N.M. Paul and W.S. Palmer), Matter and Memory (New York: Zone Books, 1988 [1896]).](/cslide/img/icons/document.png) H. Bergson (trans. N.M. Paul and W.S. Palmer), Matter and Memory (New York: Zone Books, 1988 [1896]).

H. Bergson (trans. N.M. Paul and W.S. Palmer), Matter and Memory (New York: Zone Books, 1988 [1896]).

Description:'By the time that Creative Evolution was published, Bergson had come increasingly to rely on a particular strand of scientific thinking that (he believed) accorded particularly well with his philosophy. His 1896 book Matter and Memory had introduced a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry. In Creative Evolution, however, Bergson appeared wiling to go further: biological science was to be brought back within the purview of the philosophical tradition from which (Bergson believed) it had originated.'

-

Quotes

I. van Gieson, The Correlation of Sciences in the Investigation of Nervous and Mental Disease (Utica, NY: State Hospitals Press, 1899).

I. van Gieson, The Correlation of Sciences in the Investigation of Nervous and Mental Disease (Utica, NY: State Hospitals Press, 1899).

Description:'Adherents of cellularly-distinct conceptions of neuronal connection portrayed them as confirming associationist contentions regarding the nature of psychology... In 1898, Boris Sidis and Ira van Gieson separately elaborated this thesis to account for states of sanity and insanity: in Gieson's words, 'unsoundness of mind' was caused by the 'dissociation' of the 'higher and last evolved parts of the brain, in the presence of pathogenic stimuli.'

-

Quotes

M. Foster, 'Physiology', Encyclopedia Britannica, (10th ed.) Vol. XIX. (New York: Werner, 1902), pp. 8-23.

M. Foster, 'Physiology', Encyclopedia Britannica, (10th ed.) Vol. XIX. (New York: Werner, 1902), pp. 8-23.

Description:'For amoeboid theorists, the apparent mechanical capacity of nerve cells to alter their proximity to one another presented physical confirmation of the existence of psychological associations.

In a similar way, adherents of the protoplasmic conception of neuronal connection identified mental activity with the presumed properties of this vital substance. Especially prominent amongst such adherents was the renowned physiologist Ewald Hering... As Michael Foster put it for the 1902 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 'in Hering's conception the mere condition of the protoplasm, whether it is largely built up or largely broken down, produces effects which result in a particular state of consciousness.''

-

Quotes

M. Verworn and F.S. Lee, An Outline of the Physiology of Life (London: Macmillan & Co., 1899).

M. Verworn and F.S. Lee, An Outline of the Physiology of Life (London: Macmillan & Co., 1899).

Description:'Fig. 1: Illustration of 'protoplasmic pseudopodia'. Fig. 170 from M. Verworn and F.S. Lee, An Outline of the Physiology of Life (London: Macmillan & Co., 1899).'

-

Quotes

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

Description:Main body of the essay taken from Science in Context article as follows (NB: notes removed, links added, and some phrases and passages have been changed):

'By the time that Creative Evolution was published, Bergson had come increasingly to rely on a particular strand of scientific thinking that (he believed) accorded particularly well with his philosophy. His 1896 book Matter and Memory had introduced a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry. In Creative Evolution, however, Bergson appeared wiling to go further: biological science was to be brought back within the purview of the philosophical tradition from which (Bergson believed) it had originated. This was to be achieved, he argued, through the constitution of a theory of knowledge that, because based in immediate experience, would also be a theory of life.

'Together', Creative Evolution contended, philosophy and vital science would 'solve by a method more sure, brought nearer to experience, the great problems that philosophy poses.' By thinking together a set of contentions regarding the originary nature of life with his own introspectively-derived conclusions regarding the nature of memory and experience, it would be possible to arrive at a situation in which biological and indeed all science would appear merely as 'psychics inverted'. Ultimately, living matter for Bergson evinced a psychological process which was 'in its essence... an effort to accumulate energy and then to let it flow into flexible channels, changeable in shape, at the end of which it will accomplish infinitely varied kinds of work.' Philosophical practice similarly consisted in a process of accumulation and dissimilation, but of conscious awareness. Experience alternated between an intellectual state in which the 'whole personality concentrate[d] itself', and a dream-like, 'scattered', 'intuitive' state in which the originary nature of matter became perceptible. The vital mind thus 'used' space 'like a net with meshes that can be made and unmade at will, which thrown over matter, divides it as the needs of our action demand.' The life sciences, properly interpreted, constituted an introspective investigation of the processes of extension and retraction as they manifested themselves in the living substance.

Recent historiography on relations between psychology and life science in Europe at the turn of the twentieth century suggests that the hope that Bergson held out for the latter was by no means misplaced. For example, Judy Schloegel and Henning Schmidgen point to the prominence during the final decades of the nineteenth century of a physiological tradition in which the origins of psychological existence were associated with that of the most simple known forms of organic matter; in the work of Ernst Haeckel, Max Verworn, and Alfred Binet, psychological properties such as sensation, volition and intention were discovered in apparently primordial forms of life, most notably the cell. Though these investigators differed regarding the extent to which they regarded such properties as inhering in protoplasmic or nucleic parts of cells, all agreed that each could be considered an independent psychic unit. Human psychology was the manifestation of the simultaneous action of the countless autonomously-acting individuals that composed their bodies: properly understood, mind was indeed able to dissimilate into its originary nature.

One of the most pressing questions facing those who adhered to such conceptions was that of exactly how independently-acting cellular individuals could combine to form more complex psychological wholes. Different tendencies existed within the conceptual framework of cellular individuality. One contention that gained considerable traction during the final years of the nineteenth century was the so-called 'amoeboid' theory of cellular interaction. Just as individual cells could be identified as manifesting vital capacities such as autonomous extension and contraction, each nerve-cell or 'neuron' was, in the conception of histologists such as Mathias-Marie Duval, an independently-acting contributor to the neurological whole. Ramón y Cajal suggested in a study of 1890 that nerve fibres could be seen to grow outwards from their cellular origins. Though Cajal would later renounce this view, he and like-minded theorists believed that this constituted evidence that nerve cells behaved just like amoeba in that they expanded, contracted, and moved their extremities from place to place. The possibility of psychological variation was thereby assured: by altering the proximity of each cell to one another, amoeboid movement altered the extent to which electrical nerve-impulses could be communicated. The psychologically-individual cells of the nervous system combined to create a greater whole.

Contrasting with this conception of cellular activity was an alternative, 'network'-centred vision of neurological connection. Though the notion that the body was permeated by a fibrous network of nerves through which organs communicated had been prominent in physiology prior to the nineteenth century, this had been sidelined as the cell theory had been established. In 1869 however, Thomas Henry Huxley had prominently declared protoplasm the 'physical basis of life'. First propounded by Max Schultze in 1860, it had been Haeckel who presented the most influential discussion of its relevance to psychology. As Robert Brain notes, Haeckel's contention that that protoplasm 'had the ability to receive and maintain the waveform vibrations of the external world' and thereby pass on organic characteristics from one generation to the next achieved great prominence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Haeckel further argued that a protoplasmic capacity for the reception and storage of wave-forms endowed cells with psychological capacity. Well into the twentieth century, histologists such as Camillo Golgi, Hans Held, Stephan Apáthy and Albrecht Bethe presented evidence that nerves could link together via continuously connecting organic structures. A significant strand of late-nineteenth-century physiological psychology thereby identified the variability of nervous excitation not with the properties of individual cells as such, but with the vital and extensible properties of the protoplasm that (it was held) was common to them all.

Adherents of cellularly-distinct conceptions of neuronal connection portrayed them as confirming associationist contentions regarding the nature of psychology. For example, US physician Francis Xavier Dercum argued that the 'amoeboid' expansion and retraction of individual cells underlay variously: hysteria; hypnotic and dream states; sleep; and trains of thought themselves. These latter, Dercum contended, appeared 'to follow purely mechanical lines' of association and disassociation between the sense impressions that they carried. In 1898, Boris Sidis and Ira van Gieson separately elaborated this thesis to account for states of sanity and insanity: in Gieson's words, 'unsoundness of mind' was caused by the 'dissociation' of the 'higher and last evolved parts of the brain, in the presence of pathogenic stimuli.' For amoeboid theorists, the apparent mechanical capacity of nerve cells to alter their proximity to one another presented physical confirmation of the existence of psychological associations.

In a similar way, adherents of the protoplasmic conception of neuronal connection identified mental activity with the presumed properties of this vital substance. Especially prominent amongst such adherents was the renowned physiologist Ewald Hering. Calling for physiologists to 'cease considering physiology merely as a sort of applied physics and chemistry,' Hering argued that the causes of nervous action were to be found in two independent and contradictory tendencies of protoplasmic matter. On the one hand, a tendency towards 'assimilation' could be perceived within living substance. This was balanced by an equal and opposite tendency, that towards 'dissimilation'. Where assimilation predominated, organic matter increased in activity. Where dissimilation predominated, activity decreased. There were thus 'two closely interwoven processes, which constitute the metabolism (unknown to us in its intrinsic nature) of the living substance'. The variable energetic states of protoplasm expressed itself in the nervous system as the throwing-out of countless connections between cellular bodies: 'a nerve-trunk is... a bundle of living arms which the elementary organisms of the nervous system send forth for the purpose of entering into functional connexion with one another, or of permitting the phenomena of the outside world to act upon them, or of exercising control over other organs' (see Fig. 1). As Michael Foster put it for the 1902 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 'in Hering's conception the mere condition of the protoplasm, whether it is largely built up or largely broken down, produces effects which result in a particular state of consciousness.' Sensation was not so much the consequence of impressions on sensory organs that were then conveyed to the mind via the nerves, as the establishment of sympathetic rhythms between the various realms of existence. Thus in the case of visual sensations, Hering argued that protoplasm vibrated according to the frequency of light-waves connecting with the retina. Brain recounts how at the Paris Societé de biologie, Binet and others developed similar explanatory schema to account variously for hypnotic and hysteric states, sleep, aesthetic experience, and even paranormal phenomena. Protoplasm spread both inwards and outwards from the vital mind, bringing mental life into vibratory harmony with that with which it connected.

By insisting on the active, temporally extensive nature of both bodily and psychological existence, Bergson's appeal to organic sciences was thereby aligned with a highly active research tradition within physiological science. For him, such studies as those detailed above indicated that 'life is a movement, materiality is the inverse movement, and each of these two movements is simple, the matter which forms a world being an undivided flux.' Here then was confirmation of the philosophical import of physiological investigation. To the extent that physiology confirmed the evidence of introspective insight, it presented a means by which the philosopher might demonstrate the organically creative presence of thought within the body.