- External URL

- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): Ewald HeringDate: 1898

- Current Holder(s)

-

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Quoted by

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Description:'For amoeboid theorists, the apparent mechanical capacity of nerve cells to alter their proximity to one another presented physical confirmation of the existence of psychological associations.

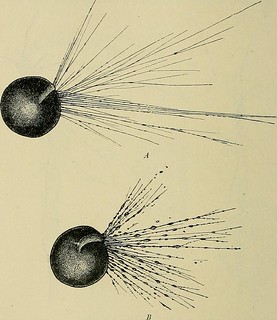

In a similar way, adherents of the protoplasmic conception of neuronal connection identified mental activity with the presumed properties of this vital substance. Especially prominent amongst such adherents was the renowned physiologist Ewald Hering. Calling for physiologists to 'cease considering physiology merely as a sort of applied physics and chemistry,' Hering argued that the causes of nervous action were to be found in two independent and contradictory tendencies of protoplasmic matter. On the one hand, a tendency towards 'assimilation' could be perceived within living substance. This was balanced by an equal and opposite tendency, that towards 'dissimilation'. Where assimilation predominated, organic matter increased in activity. Where dissimilation predominated, activity decreased. There were thus 'two closely interwoven processes, which constitute the metabolism (unknown to us in its intrinsic nature) of the living substance'. The variable energetic states of protoplasm expressed itself in the nervous system as the throwing-out of countless connections between cellular bodies: 'a nerve-trunk is... a bundle of living arms which the elementary organisms of the nervous system send forth for the purpose of entering into functional connexion with one another, or of permitting the phenomena of the outside world to act upon them, or of exercising control over other organs' (see Fig. 1)... Sensation was not so much the consequence of impressions on sensory organs that were then conveyed to the mind via the nerves, as the establishment of sympathetic rhythms between the various realms of existence. Thus in the case of visual sensations, Hering argued that protoplasm vibrated according to the frequency of light-waves connecting with the retina.'

-

Quoted by

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

Description:'adherents of the protoplasmic conception of neuronal connection identified mental activity with the presumed properties of this vital substance. Especially prominent amongst such adherents was the renowned physiologist Ewald Hering. Calling for physiologists to 'cease considering physiology merely as a sort of applied physics and chemistry,' Hering argued that the causes of nervous action were to be found in two independent and contradictory tendencies of protoplasmic matter. [note: 'E. Hering, 'On the Theory of Nerve Activity', The Monist 10 (2) (1900), pp. 167-187, on p. 169.'] On the one hand, a tendency towards 'assimilation' could be perceived within living substance. This was balanced by an equal and opposite tendency, that towards 'dissimilation'. Where assimilation predominated, organic matter increased in activity. Where dissimilation predominated, activity decreased. There were thus 'two closely interwoven processes, which constitute the metabolism (unknown to us in its intrinsic nature) of the living substance'. [note: 'E. Hering (trans. F.A. Welby), 'Theory of the Functions of Living Matter', Brain 20 (1-2) (1897), pp. 232-258, on pp. 232-233.'] The variable energetic states of protoplasm expressed itself in the nervous system as the throwing-out of countless connections between cellular bodies: 'a nerve-trunk is... a bundle of living arms which the elementary organisms of the nervous system send forth for the purpose of entering into functional connexion with one another, or of permitting the phenomena of the outside world to act upon them, or of exercising control over other organs'. [note: 'Hering, 'On the Theory of Nerve Activity', pp. 177-178.'] As Foster put it for the 1902 edition of the Encyclopedia Brittannica, 'in Hering's conception the mere condition of the protoplasm, whether it is largely built up or largely broken down, produces effects which result in a particular state of consciousness.' [note: 'M. Foster, 'Physiology', in Encyclopedia Britannica, (10th ed.) Vol. XIX. (New York: Werner, 1902), pp. 8-23, on p. 22.'] Sensation was not so much the consequence of impressions on sensory organs that were then conveyed to the mind via the nerves, as the establishment of sympathetic rhythms between the various realms of existence. Thus in the case of visual sensations, Hering argued that protoplasm vibrated according to the frequency of light-waves connecting with the retina. [note: 'Hering, 'On the Theory of Nerve Activity', pp. 183, 186.'] Brain recounts how at the Paris Societé de Biologie, Binet and others developed similar explanatory schema to account variously for hypnotic and hysteric states, sleep, aesthetic experience, and even paranormal phenomena. [note: 'R.M. Brain, 'Materialising the Medium: Ectoplasm and the Quest for Supra-Normal Biology in Fin-de-Siècle Science and Art', in A. Enns and S. Trower (eds.), Vibratory Modernism (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), pp. 115-144, on pp. 125-127.'] Protoplasm spread both inwards and outwards from the vital mind, bringing mental life into vibratory harmony with that with which it connected.'

Relevant passages from Hering:

'Let us cease considering physiology merely as a sort of applied physics and chemistry and thus avoid arousing the justifiable opposition of those who believe it to be an idle task to seek an exhaustive explanation of the living from the dead. Life can be fully understood only from life, and a Physics and a Chemistry which have sprung solely from the domain of inanimate nature, and which therefore apply solely to inanimate nature, are adequate only to the explanation of such things as are common to the living and the dead.' (169)

'Every nerve-fiber, according to this theory, is associated in such wise with a nerve-cell as to form with it a single elementary organism only; and the living substance of that organism, which is collected in more abundant quantities about the nucleus of the nerve cell, is continued into the fibers. Accordingly, the nerve-fibers would be integral constituents of these elementary structures of the nervous system, or neurons, as they are called. On this theory, the idea is quite natural to ascribe to the fibers which continue the cells the same specific differences which physiologists were obliged to assign to the nerve-cells of the various cerebral centers. [note: 'I offer no opinion as to the correctness of the histological doctrine of neurons. I lay it at the foundation of the present discussion because my theory needs some definite histological substratum'] But as soon as we do this, we no longer have before us cells which, though capable of performing different tasks, are yet connected by filaments having quite the same functions, but we have elementary organisms whose specific or individual dissimilarity extends to their remotest filar prolongations. A nerve-trunk is no longer a mere bundle of conducting wires disengaging different sorts of effects according to the kind of apparatus with which they are connected at their termini and being at the same time in their own specific function absolutely of the same kind; but it is a bundle of living arms which the elementary organisms of the nervous system send forth for the purpose of entering into functional connexion with one another, or of permitting the phenomena of the outside world to act upon them, or of exercising control over other organs like the muscles and the glands. And in each one of these arms a quite special kind of life is active, corresponding precisely to the neuron to which the nerve-fiber belongs. The conducting path which unites a sense-organ with the cerebral cortex, or the latter with a muscle, appears as a chain of living individuals of which every member, although always dependent upon its neighbors, still leads a separate life, the specific character of which is generally different in the different parts of the nervous system. Even in the neurons of the same group it is not absolutely the same, but bears in each of them a more or less individual stamp.' (177-178)

'Rightly have the opponents of the doctrine of the specific energies of the sensory nerves pronounced against the view of a life long unalterable constancy of function of the nerves, but they went, as I conceive, too far when they contested the congenitally different and special nature of the individual sensory nerves, accepted the indifference of function of all sensory fibers of the new-born, and regarded all functional differences of nerve-fibers, which are the phylogenetic acquisition of innumerable generations, merely as the result of an adaptation to heterogeneous, individual sensory stimuli during the post-embryonic period.

Of course after birth the influences of the external world belong to the conditions of the further normal development of the whole body, and the sensory stimuli especially are indispensable conditions of development of the nervous apparatus of our sense-organs. But light, for example, finds in the eye of the new-born babe not a nerve-substance from which, so to speak, anything whatever can be made; in other words, a substance which, if it could be transposed from the eye into the ear or into the tongue could be educated by the sound-waves to be a medium of auditory sensations, or by gustatory stimuli to be a medium of taste-sensation.

As the germ sprouting from the earth needs light to become a green plant, so in the new-born babe the neuron in the eye needs light, and the neuron in the ear the sound stimulus, to complete its course of development; but just as light never makes the fungus green, so it could never make the neurons of the ear see if they should be transplanted into the eye. As I take it, the neurons of our eye are not merely educated, but are born for seeing, and like wise those of our ear for hearing.

...

Writers love to compare the nerve-fibers with telegraph or telephone wires, and they will consequently, perhaps, point to the endless multiplicity of things which can be transmitted through wires of exactly the same kind. The comparison is seductive, for if spun out farther, it seems suited to solve all difficulties at a single stroke.

In place of the undoubtedly "obscure" specific or individual "qualities" of the nervous processes of which I have spoken, appears a multiplicity of oscillations of different temporal and spatial form, of which the nerve-substance is the mere vehicle. But one finally comes to exactly the same result with this comparison as I do. For one must admit that neither in all nerve-fibers is the same oscillation-form always transmitted, nor is every individual nerve fiber susceptible of all the oscillation-forms which are possible to the nerve-substance generally, but only of those to which it can respond.

What we have named the specific energy of the fibers or cells reappears here as special resonance-capacities corresponding to definite oscillation-forms. What we formerly called an inborn, acquired or individual characteristic, becomes here the pitch; and, as with us, the specific excitabilities, so here the resonance and previous attunement of the neurons determine the paths in the nervous system which a given oscillation-form shall enter upon.' (183, 186)