- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): Henri-Louis BergsonDate: 1896

- Current Holder(s)

-

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cited by

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

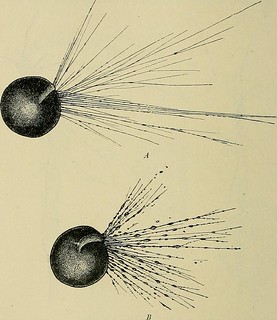

Description:'Starting with his doctoral dissertation (1889), Bergson consistently opposed what he characterized as the 'mathematical deduction' of conventional scientific perception to the spontaneous appearance of the thought-images that he contended constituted philosophically-lived experience. He complained that the 'scientific realism' adhered to by mechanism-reliant analysts of nature was unable to reconcile two radically different claims to which it adhered: firstly, that nature in fact consisted in material changes within space that could be reduced to a series of capturable moments; secondly, that these moments could be arranged in consciousness as a set of natural objects - that each captured moment could be retained and re-arranged into a coherent, calculable whole. [note: 'H. Bergson (trans. F.L. Pogson) Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Data of Consciousness (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1910), e.g. pp. 75-79; H. Bergson (trans. N.M. Paul and W.S. Palmer), Matter and Memory (New York; Zone Books, 1988), e.g. pp. 69-71.']'

'Matter and Memory (1896)... introduced a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry. [note: 'Bergson, Matter and Memory, esp. pp. 22-28.']'

'Ultimately, living matter evinced a psychological process which was 'in its essence... an effort to accumulate energy and then to let it flow into flexible channels, changeable in shape, at the end of which it will accomplish infinitely varied kinds of work.' [note: 'Bergson, Creative Evolution, p. 253-254. See also Bergson, Matter and Memory, e.g. pp. 28- 31, 41-46.']'

'Bergson not only asserted the scientific relevance of his own views regarding life and mind, however, but argued for the superiority of his own approach over that with which he contrasted it. To do so, he employed a vivid metaphor. The exact sciences, Bergson suggested, had adopted and expanded out of all proportion a tendency within classical philosophy (exemplified by the paradoxes of Zeno of Elea) in which phenomena were considered in terms of series of isolated moments. [note: 'Bergson, Creative Evolution, pp. 308-313. See also Bergson, Matter and Memory, pp. 188-193.']'

The insight of Bergson's most relevant to present-day historical practice then is not that relating to the primacy of intuition in psychological experience, or an organic vital force, or even a temporal absolute, but rather his insistence that all intellectual endeavour simultaneously responds to and constitutes material change (i.e. occurs within history). With Bergson, we cannot expect either the current contentions of psychology, biology or physics, correct ethical or aesthetic judgement, or indeed the claims of historians, to remain absolutely stable. Most importantly, we certainly cannot expect the currently accepted means by which knowledge in any of these fields (or their progeny) is established to persist indefinitely. Bergson's philosophy speaks to current modes of historical investigation - not least in its assertion that all experience (including that on which the claims of physical science are based) is in some sense that of a past. [note: 'Bergson, Matter and Memory, pp. 71-76 and passim. For Bergson's early presence in British historiography see C. Kerslake, 'Becoming Against History: Deleuze, Toynbee, and Vitalist Historiography', Parrhesia 4 (2008), pp. 17-48, esp. pp. 26-31.']'

-

Quoted by

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Description:'By the time that Creative Evolution was published, Bergson had come increasingly to rely on a particular strand of scientific thinking that (he believed) accorded particularly well with his philosophy. His 1896 book Matter and Memory had introduced a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry. In Creative Evolution, however, Bergson appeared wiling to go further: biological science was to be brought back within the purview of the philosophical tradition from which (Bergson believed) it had originated.'