- External URL

- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): Robert Michael BrainDate: 2013

- Current Holder(s)

-

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cites

C.S. Sherrington, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1906).

C.S. Sherrington, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1906).

Description:'In the 1890s the nerve junction was still understood through the amoeboid theory of neuronal mobility, which held that neurons made functional contacts through pseudopodal movements of the protoplasm of nerve cells. [note: 'Sandra E. Black, 'Pseudopods and Synapses: the Amoeboid Theories of Neuronal Mobility and the Early Formation of the Synapse Concept. 1894-1900', Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55 (1) (1981): 34-58.'] The theory grew in part from the visual evidence: improved microscopy had revealed a new image if neurons as individual cells, with limited movements of extension and contraction that seemed to facilitate inter-neuronal conduction at the 'synapse' (the term itself, from the Greek for 'clasp', was coined by Charles Sherringotn to express this amoeboid movement). [note: 'Charles S. Sherrington coined the term 'synapse' for sections he authored in the seventh edition of Foster's Textbook of Physiology (1997) [sic] as an apt illustration of the amoeboid theory. Interestingly, the term synapse stood, even when the view of the neuronal junction changed, largely through Sherrington's own efforts. To compare Sherrington's amoeboid hypothesis and his later, canonical account of the synapse as a fixed, transverse membrane, see C.S. Sherrington, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System (New York: Scribner's Sons, 1906),']'

-

Cites

S.E. Black, '"The Osler Medal Essay": Pseudopods and Synapses: The Amoeboid Theories of Neuronal Mobility and the Early Formation of the Synapse Concept', Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55 (1981), pp. 34-58.

S.E. Black, '"The Osler Medal Essay": Pseudopods and Synapses: The Amoeboid Theories of Neuronal Mobility and the Early Formation of the Synapse Concept', Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55 (1981), pp. 34-58.

Description:'In the 1890s the nerve junction was still understood through the amoeboid theory of neuronal mobility, which held that neurons made functional contacts through pseudopodal movements of the protoplasm of nerve cells. [note: 'Sandra E. Black, 'Pseudopods and Synapses: the Amoeboid Theories of Neuronal Mobility and the Early Formation of the Synapse Concept. 1894-1900', Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55 (1) (1981): 34-58.']' (12)

-

Cited by

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Description:'Brain recounts how at the Paris Societé de biologie, Binet and others developed similar explanatory schema to account variously for hypnotic and hysteric states, sleep, aesthetic experience, and even paranormal phenomena. Protoplasm spread both inwards and outwards from the vital mind, bringing mental life into vibratory harmony with that with which it connected.'

-

Cited by

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

Description:For Hering, 'sensation was not so much the consequence of impressions on sensory organs that were then conveyed to the mind via the nerves, as the establishment of sympathetic rhythms between the various realms of existence. Thus in the case of visual sensations, Hering argued that protoplasm vibrated according to the frequency of light-waves connecting with the retina (Hering 1900, 183, 186). Brain recounts how at the Paris Société de Biologie, Binet and others developed similar explanatory schema to account variously for hypnotic and hysteric states, sleep, aesthetic experience, and even paranormal phenomena (Brain 2013, 125-127). Protoplasm spread both inwards and outwards from the vital mind, bringing mental life into vibratory harmony with that with which it connected.'

Relevant passage from Brain:

'Richet's notion of ectoplasm offered a deeper biological account of these [paranormal] phenomena. From the psychologists' perspective it was more than just the sliminess of these materialisations that suggested that they were protoplasmic prima materia. Richet thought that ectoplasm was but an extreme instance of normal nerve physiology: he regarded the extrusions as a consequence of a certain protoplasmic idea of nervous action under the heightened or supra-normal conditions of the spiritualist séance. All spiritual mediums, Richet claimed, were hysterics, and the trance states of séances reoresented a state of hyper-stimulation of the nervous system. In these states the nerve junction overshot its normal function, exuding excess protoplasm through orifices and other sites on the body, creating yet another form of dédoublement of the medium's self. To better understand this, it is necessary to explain the so-called 'amoeboid theory of neuronal mobility' which reigned at the end of the nineteenth century.

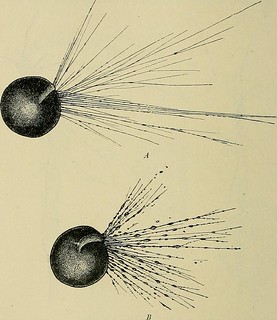

In the 1890s the nerve junction was still understood through the amoeboid theory of neuronal mobility, which held that neurons made functional contacts through pseudopodal movements of the protoplasm of nerve cells. [note: 'Sandra E. Black, 'Pseudopods and Synapses: the Amoeboid Theories of Neuronal Mobility and the Early Formation of the Synapse Concept. 1894-1900', Bulletin of the History of Medicine 55 (1) (1981): 34-58.'] The theory grew in part from the visual evidence: improved microscopy had revealed a new image if neurons as individual cells, with limited movements of extension and contraction that seemed to facilitate inter-neuronal conduction at the 'synapse' (the term itself, from the Greek for 'clasp', was coined by Charles Sherringotn to express this amoeboid movement). [note: 'Charles S. Sherrington coined the term 'synapse' for sections he authored in the seventh edition of Foster's Textbook of Physiology (1997) [sic] as an apt illustration of the amoeboid theory. Interestingly, the term synapse stood, even when the view of the neuronal junction changed, largely through Sherrington's own efforts. To compare Sherrington's amoeboid hypothesis and his later, canonical account of the synapse as a fixed, transverse membrane, see C.S. Sherrington, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System (New York: Scribner's Sons, 1906),'] Neuron cells bore striking visual resemblance to the pseudopods of amoebae and leukocytes, prompting enthusiastic speculation and research into the idea that the neuronal transmission might be best understood through the behaviour of rhizopods and other univellular organisms (Figure 5.7). The amoeboid theory of the extension and retraction of neurin terminations suggested a mechanism for increasing or decreasing the gap at the neuronal junction. The 'alteration of the gap' was used to explain all sorts of conditions, especially sleep (which occurred when contact was gradually suspended) and a range of trance, hypnotic, and drug-induced states.

This theory of the nerve synapse came under attach by the Spaniard Santiago Ramón y Cajal and his allies after the turn of the century. But [during] the 1890s the theory underwrote a lively amount of research and speculation, especially in the Paris Société de Biologie, of which Richet was an active member. [note: 'For the French debate see L. Azoulet, 'Psychologie histologique et texture du système nerveux', L'année psychologique 2 (1895): 255-94; Charles Pupil, Le Neurone et les hypothèses histologique de son mode de fonctionnnement. [sic] Théorie histologique sy sommeil (Paris: Steinhall, 1896); Micheline Stefanowska, 'Les appendices terminaux de dentrites cérébraux et leurs différents états psychologiques', Travaux de la laboratoire de l'Onstitut Solvay (Bruxelles, 1897), pp. 1-58; R. Deyber, L'Etat actuel de la question d'amoeboïsme (Paris: Steinhal, 1897); Alfred Binet, 'Revue Générale sur l'amoeboïsme du système nerveux', L'année psychologique 4 (1) (1897): 438-49.'] Richet was among the scientists who believed that it would provide the key to understanding a wide range of neurological and psychological questions, including hypnotic and hysteric states, aesthetic experience, a theort of sleep (through cyclical inhibitory withdrawal of the dendritic pseudopods) and various forms of 'exteriorization of sensibility' (through special forms of prolonged dynamogenous excitation.

If the amoeboid theory of extension suggested an explanation of trance states, those states in turn might prove a special opportunity for studying aspects of human psycho-physiolgogy under unique conditions. Richet conjectured that sprit mediums, placed in a deep trance state in which all voluntary psychological responses were suspended, experience the extrojection of 'sarcodic expansions' or protoplasmic pseudopods beyond the material limits of the body. [note: 'The term 'sarcode' was a French term for protoplasm, coined by Félix Dujardin in 1835, which remained in currenct through the nineteenth century. See Laurent Loisin, Qu'est-ce que le néolamarckism? Les Biologistes français et la question de l'evolution des espéces (Paris: Vuibert, 2010), pp. 72-4.']

Materialisation are the sarcodic expansions leaving the human body of the mediums absolutely like the pseudopodic expansion leaves the amoeba cell. All zoologists know that the amoeba is a sarcode that can project itself outside in order to seize bits of alimentation and to incorporate neighbouring objects. In the same way, during the mediumistic trance, the body of the medium can emit fluidic filaments, expansions, in the form of clouds, veils, or plant stalks, which then organise themselves and completely take the appearance of human limbs.' [note: 'Charles Richet, Thirty Years of Psychical Research: Being a Treatise on Metaphysics, trans. Stanley de Brath (New York: Macmillan, 1923), p. 618.']