- External URL

- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): Laura OtisDate: 2001

- Current Holder(s)

-

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cited by

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

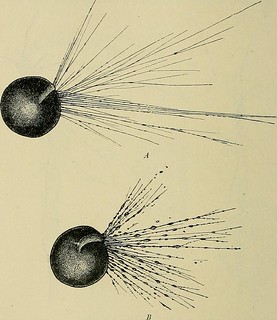

Description:'by altering the proximity of each cell to one another, amoeboid movement altered the extent to which electrical nerve-impulses could be communicated. The psychologically-individual cells of the nervous system combined to create a greater whole.

Contrasting with this conception of cellular activity was an alternative, 'network'-centred vision of neurological connection. Though the notion that the body was permeated by a fibrous network of nerves through which organs communicated had been prominent in physiology prior to the nineteenth century, this had been sidelined as the cell theory had been established. In 1869 however, Thomas Henry Huxley had prominently declared protoplasm the 'physical basis of life'. First propounded by Max Schultze in 1860, it had been Haeckel who presented the most influential discussion of its relevance to psychology. As Robert Brain notes, Haeckel's contention that that protoplasm 'had the ability to receive and maintain the waveform vibrations of the external world' and thereby pass on organic characteristics from one generation to the next achieved great prominence during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.'

-

Cited by

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

Description:'The second part of the paper highlights however that it was not the implausibility for physiological researchers of Bergson’s claims that had the most significant implications for the status of his contentions, but rather a set of epistemological and institutional changes that occurred within physiology and psychology. The establishment of technical epistemic commitments within these sciences during the late nineteenth century contributed to the emergence of disciplinary boundaries between these fields. Drawing on recent historical work addressing the roles of media tools in physiological and psychological investigation (de Chadarevian 1993; Brain and Wise 1994; Otis 2001; Schmidgen [2009] 2014; Cat 2013; Brain 2015), it shows how the engagement by Sherrington and others with devices that emerged from within the cinema of attractions contributed to the break-down of the physiological psychological presumption that philosophic and physiologic investigation shared common categories of analysis.'

'by altering the proximity of each cell to one another, amoeboid movement altered the extent to which electrical nerve-impulses could be communicated. The psychologically-individual cells of the nervous system combined to create a greater whole.

Contrasting with this conception of cellular activity was an alternative, 'network'-centred vision of neurological connection (Otis 2001, 55-69).'