- External URL

- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): Henri-Louis BergsonDate: 1907

- Current Holder(s)

-

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cites

H. Bergson, 'Brain and Thought: a philosophical illusion', in H. Bergson (trans. H. Wilden Carr) Mind-energy: lectures and essays (New York, 1920), pp. 231-255.

H. Bergson, 'Brain and Thought: a philosophical illusion', in H. Bergson (trans. H. Wilden Carr) Mind-energy: lectures and essays (New York, 1920), pp. 231-255.

Description:'the psycho-physiologist who affirms the exact equivalence of the cerebral and the psychical state, who imagines the possibility, for some superhuman intellect, of reading in the brain what is going on in consciousness, believes himself very far from the metaphysicians of the seventeenth century, and very near to experience. Yet experience pure and simple tells us nothing of the kind. It shows us the interdependence of the mental and the physical, the necessity of a certain cerebral substratum for the psychical state—nothing more. From the fact that two things are mutually dependent, it does not follow that they are equivalent. Because a certain screw is necessary to a certain machine, because the machine works when the screw is there and stops when the screw is taken away, we do not say that the screw is the equivalent of the machine. For correspondence to be equivalence, it would be necessary that to any part of the machine a definite part of the screw should correspond—as in a literal translation in which each chapter renders a chapter, each sentence a sentence, each word a word. Now, the relation of the brain to consciousness seems to be entirely different. Not only does the hypothesis of an equivalence between the psychical state and the cerebral state imply a downright absurdity, as we have tried to prove in a former essay, but the facts, examined without prejudice, certainly seem to indicate that the relation of the psychical to the physical is just that of the machine to the screw. To speak of an equivalence between the two is simply to curtail, and make almost unintelligible, the Spinozistic or Leibnizian metaphysic.' (354-355)

-

Cited by

C. Kerslake, 'Becoming Against History: Deleuze, Toynbee, and Vitalist Historiography', Parrhesia 4 (2008), pp. 17-48.

C. Kerslake, 'Becoming Against History: Deleuze, Toynbee, and Vitalist Historiography', Parrhesia 4 (2008), pp. 17-48.

Description:'Bergson himself did not apply his vitalistic theory of biological evolution and development, first developed in Creative Evolution (1907), directly to the field of human evolution and the history of civilization.' (26)

'Lindsay stressed Bergson’s idea (voiced in Creative Evolution) that intuition “must be, like art, disinterested, or rather, like art, interested only in its object”, and that “intuition implies sympathy, in the sense at least of caring enough about things to know them in their own nature.” [note: 'Ibid, 236; cf. 221.']' (26)

'Toynbee refers to Bergson explicitly a number of times, often citing large chunks of his writings. The first volume of the Study, published in 1934, has two citations of Bergson’s Creative Evolution; in the third volume (published in the same year), there are a number of citations and references to Bergson’s Two Sources of Morality and Religion, published two years previously in 1934. ['note: See Toynbee, Study, 3: 118-119, 125, 181-85, 225-6, 231-37, 243-47, 254-56. McNeill even suggests that Toynbee’s basic version of the Bergsonian dualism between ‘life’ and ‘mechanism’ in an early essay from 1907-11 remains his elementary intellectual framework until his latest works, when the dualism finally takes centre stage (McNeill, Arnold Toynbee, 267). The opening of Toynbee’s student essay, ‘The Machine: A Problem of Dualism’, is worth quoting: “The whole universe – my consciousness, my body, my safety razor – is all a machine, and the paradox of the machine is inherent in the whole of it. It partakes of two orders of being … Life, which we know because that is what we are, and that other, which we do not know because we are not it, but which is Life’s environment and object of activity” (Toynbee Papers, Juvenilia, Bodleian Library, cited in McNeill, Arnold Toynbee, 28). Toynbee goes on that every success achieved by Life induces its opposite, ‘mechanization’. McNeill paraphrases: “In becoming conscious, ‘Life’ devitalizes itself; language becomes mechanical through grammar; morals harden into law and custom as a result of mechanical application to infinitely varying circumstance” (ibid). The young Toynbee here grasps Bergsonian vitalism ‘from within’, divining the basic Bergsonian spatiotemporal dynamism.']' (27)

'Instead of explicitly justifying why we should be more afraid of the Apathetic than the Pathetic Fallacy (as we will see, Toynbee can easily be accused of an almost frenzied flaunting of the latter), Toynbee immediately goes on to make his first reference to Bergson, implicitly recalling Lindsay’s vision of the historian’s consciousness. The objection to the Apathetic Fallacy, it turns out, is rooted in Bergson’s critique of the limitations of intelligence (in Creative Evolution):

It is conceivable that, as Bergson suggests, the mechanism of our intellect is specifically constructed so as to isolate our apprehension of Physical Nature in a form which enables us to take action upon it. Yet even if this is the original structure of the human mind, and if other methods of thinking are in some sense unnatural, there yet exists a human faculty, as Bergson goes on to point out, which insists, not upon looking at Inanimate Nature, but upon feeling Life and feeling it as a whole. This deep impulse to envisage and comprehend the whole of Life is certainly immanent in the mind of the historian. [note: 'Study, 1:8. In the footnotes, Toynbee refers to chapter III of Creative Evolution (also important for Deleuze; cf. the 1960 ‘Cours inédit de Gilles Deleuze sur la chapitre III de L’Évolution creatricé’, in F. Worms, ed., Annales bergsoniennes II: Bergson, Deleuze, la phénoménologie. Paris, PUF, 2004).']'

(27-28)

-

Quoted by

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Henri Bergson's Physiological Psychology: Vitalism and Organicism at the Start of the Twentieth Century

Description:'It has long been recognized that the early-twentieth-century philosopher Henri Bergson placed particular emphasis on a 'vitalist' interpretation of biology. Many of his critics, including George Santanaya, Julian Huxley, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, identified Bergson's appeal to an 'élan vital' (most prominently made in his 1907 Creative Evolution) with a problematically unscientific or mystical attitude towards the world...

By the time that Creative Evolution was published, Bergson had come increasingly to rely on a particular strand of scientific thinking that (he believed) accorded particularly well with his philosophy. His 1896 book Matter and Memory had introduced a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry. In Creative Evolution, however, Bergson appeared wiling to go further: biological science was to be brought back within the purview of the philosophical tradition from which (Bergson believed) it had originated. This was to be achieved, he argued, through the constitution of a theory of knowledge that, because based in immediate experience, would also be a theory of life.

'Together', Creative Evolution contended, philosophy and vital science would 'solve by a method more sure, brought nearer to experience, the great problems that philosophy poses.' By thinking together a set of contentions regarding the originary nature of life with his own introspectively-derived conclusions regarding the nature of memory and experience, it would be possible to arrive at a situation in which biological and indeed all science would appear merely as 'psychics inverted'. Ultimately, living matter for Bergson evinced a psychological process which was 'in its essence... an effort to accumulate energy and then to let it flow into flexible channels, changeable in shape, at the end of which it will accomplish infinitely varied kinds of work.' Philosophical practice similarly consisted in a process of accumulation and dissimilation, but of conscious awareness. Experience alternated between an intellectual state in which the 'whole personality concentrate[d] itself', and a dream-like, 'scattered', 'intuitive' state in which the originary nature of matter became perceptible. The vital mind thus 'used' space 'like a net with meshes that can be made and unmade at will, which thrown over matter, divides it as the needs of our action demand.' The life sciences, properly interpreted, constituted an introspective investigation of the processes of extension and retraction as they manifested themselves in the living substance.'

'though we should acknowledge the scientific plausibility of Bergson's thinking in 1907, it should also be noted that Bergson continued to adhere to his vitalist conclusions even as the contentions to which they appealed fell out of biological fashion.'

-

Quoted by

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

Description:' On the 26th of May 1911, the philosopher Henri Bergson gave a lecture to a packed hall at the University of Oxford. Bergson was at the height of his powers: his 1907 Creative Evolution had catapulted him into into the consciousness not only his native France, but that of a growing international band of followers.'

In 1922, 'Henri Piéron suggested there that... Bergson's 'duration' (the name he gave to his own conception of time) could be identified with an experimentally demonstrable temporal experience – was in fact a psychological phenomenon entirely separate from physical time, just as Einstein had suggested.

In response to these challenges, Bergson began to re-consider the relation between his philosophy and the sciences. Though he sought to remain open to the conclusions of experimental endeavour, his approach to science as a whole became more circumspect. Creative Evolution had confidently asserted the harmony of its appeal to an introspectively-derived 'duration' with emerging biological and psychological research. Duration and Simultaneity (1922) would in contrast cast philosophy and physical science as 'unlike disciplines... meant to implement each other' (Bergson [1922] 1999, xxvii; Canales 2015, 14).'

' Sherrington's interest in cinematographs can be identified with three circumstances that played critical roles in his career as a physiologist, addressed here in turn. The first, that of Sherrington's educational background and epistemic commitments regarding physiological research, serves to highlight the extent to which Bergson's identification of physical investigation with an artificially cinematographic 'series of snapshots' (Bergson [1907] 1911, 305) was justified in the case of much late nineteenth-century physiology.'

'Though there is no evidence that Bergson was particularly interested in the minutiae of physiological research as it was practised in Britain during the 1880s, it is certain that he identified psychological psychology as it had been expounded by such British writers as Herbert Spencer with a particularly problematic philosophical trend. Bergson opposed what he called Spencer's 'false evolutionism', which he identified with what he characterized as the latter's belief that it was possible to reduce the entirety of nature to 'fragments'. Furthermore, Bergson found the more general associationist claims of which Spencer's philosophy partook unconvincing (Bergson [1907] 1911, xiii).'

'By 1907, Bergson had come to rely on a particular strand of scientific thinking that (he believed) accorded more closely with his philosophy than did the claims of mechanists. Matter and Memory had conveyed a conception of existence in which memorial experience transcended both subjective ('idealist') and objective ('realist') enquiry (Bergson [1896] 1988, 69-71). By the time Creative Evolution came to be published however, Bergson was willing to go further: biological science was to be returned within the purview of philosophy, as it had been in classical European thought. This was to be achieved, he argued, through the constitution of a theory of knowledge that, because based in immediate experience, would also be a theory of life. 'Together', he contended, these theories would 'solve by a method more sure, brought nearer to experience, the great problems that philosophy poses.' By thinking together a set of contentions regarding the originary nature of life with his own introspectively-derived conclusions regarding the nature of memory and experience, it would be possible to arrive at a situation in which biological and indeed all science would appear merely as 'psychics inverted.' Ultimately, living matter evinced a psychological process which was 'in its essence... an effort to accumulate energy and then to let it flow into flexible channels, changeable in shape, at the end of which it will accomplish infinitely varied kinds of work' (Bergson [1907] 1911, quotes on xiii, 202 and 253-254. See also idem [1896] 1988, e.g. 28-31 and 41-46). Philosophical practice similarly consisted in a process of accumulation and dissimilation, of conscious awareness. Philosophically-lived experience should alternate between an intellectual state in which the 'whole personality concentrate[s] itself', and a dream-like, 'scattered', 'intuitive' state in which the originary nature of matter becomes perceptible. The vital mind thus 'uses' space 'like a net with meshes that can be made and unmade at will, which thrown over matter, divides it as the needs of our action demand' (Bergson [1907] 1911, 201-202). The life sciences, properly interpreted, constituted an introspective investigation of the processes of extension and retraction as they manifested themselves in the living substance.'

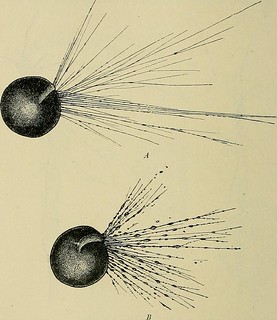

'By insisting on the active, temporally extensive nature of both bodily and psychological existence, Bergson's appeal to organic sciences was thereby aligned with a highly active research tradition within physiological science. For him, such studies as those detailed above indicated that 'life is a movement, materiality is the inverse movement, and each of these two movements is simple, the matter which forms a world being an undivided flux' (Bergson [1907] 1911, 249). Just as the philosopher brought thought-images into contact with one another, protoplasm formed psychic connections amongst material nature. Here then was confirmation of the philosophical import of physiological investigation: to the extent that physiology confirmed the evidence of introspective insight, it presented a means by which the philosopher might demonstrate the organically creative presence of thought within the body.

Bergson not only asserted the scientific relevance of his own views regarding life and mind, however, but argued for the superiority of his own approach over that with which he contrasted it. To do so, he employed a vivid metaphor. The exact sciences, Bergson suggested, had adopted and expanded out of all proportion a tendency within classical philosophy (exemplified by the paradoxes of Zeno of Elea) in which phenomena were considered in terms of series of isolated moments (Bergson [1907] 1911, 308-313. See also Bergson [1896] 1988, 188-193). The fallacy of this tendency, Bergson suggested, was revealed in the mechanics of cinematography. Conscious experience had been conceived during the nineteenth century as an automatic, passive recording device that captured a series of images as they passed before it. Reconstituting or replaying this series in memory created an illusion of change. But such re-constitution was only that: an illusion. Once, through an examination of the cinematographic mechanism, one became aware of the illusory nature of serial sensation, it would be possible to attain a truly philosophic sense of time and nature (Bergson [1907] 1911, 304-308). Introspection shorn of its cinematographic presumptions would reveal that life and mind were not an agglomeration of innumerable isolated elements and moments, but a single, flowing continuity of image-relations that could not be differentiated without loss of awareness of the whole.'