- External URL

- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): Otto Fritz Frankeau LeytonDate: 1897

- Current Holder(s)

-

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cites

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Reciprocal Action in the Retina as studied by means of some Rotating Discs', Journal of Physiology 21 (1) (1897), pp. 33-54.

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Reciprocal Action in the Retina as studied by means of some Rotating Discs', Journal of Physiology 21 (1) (1897), pp. 33-54.

Description:'Recently Sherrington [note: This Journal, XXI. p. 38. 1897.'] has shown that flicker does not depend on frequency of alternation and physical luminosity alone, but also on apparent or physiological luminosity, and that simultaneous contrast as well as successive contrast plays an important part. It is due to this phenomenon I believe that the difference between the two curves fig. 1 and fig. 2 exists.' (402)

-

Cites

F. Arago, Ouvres complètes de François Arago (Paris and Leipzig, 1854).

F. Arago, Ouvres complètes de François Arago (Paris and Leipzig, 1854).

Description:'Alteration of luminosity without altering the nature of the source of light was easily accomplished by utilising a slight modification of a method suggested by Arago [note: 'Œuvres de Fr. Arago X. pp. 184-224. 1858.'], which depends upon the inclination of two Nicol's prisms. I compared this method of observation with that of the square of the distance of the source from the screen and found that the curves drawn as results of observations were similar.' (398)

-

Cites

F. Schenck, 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Pflüger's Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 64 (3-4) (1896), pp. 165-178.

F. Schenck, 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Pflüger's Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 64 (3-4) (1896), pp. 165-178.

Description:'Fick found that under certain conditions 170 alternations might be necessary to produce fusion; this was the case when parallel lines were drawn on a drum which was rotated around an axis parallel to the lines: if, however, the observations were made through a slit no flicker was seen above 40 per second.

Baader [note: 'Dissert. Freiberg, 1891 (quoted from Schenk).'] experimenting independently made similar observations, and came to the conclusion that the size of the field of vision was a factor that must be taken into consideration when determining the speed of alternation necessary to produce fusion.' (396)

Schenk [note: 'Pflüger's Archiv LXIV. p. 165. 1896.'] has recently taken up the question [of variations of rates at which flicker ceases under different experimental conditions], and found that in his own case fusion occurred when making observations through a definite aperture, on rotating discs with a variable number of black sectors, at approximately the same speed in all cases; a variation in the same direction as found by Filehne, Fick and Baader occurred in observations made by Schenk's co-observer Schmidt.' (397)

-

Cites

K.E. von Schafhäutl, 'Abbildung und Beschreibung des Universal-Vibrations-Photometer', Abh. der Math.-Phys. CI. d. k. Bayerischen Akad. d. Wissen. München 7 (c.1854), pp. 465-497.

K.E. von Schafhäutl, 'Abbildung und Beschreibung des Universal-Vibrations-Photometer', Abh. der Math.-Phys. CI. d. k. Bayerischen Akad. d. Wissen. München 7 (c.1854), pp. 465-497.

Description:'When the eye is subjected to an alternation of stimuli of a frequency below a certain limit, the sensation of flicker with the accompanying inference of a discontintuous source of light, is produced.

Schafhäutl [note: Akad. d. Wiss. München VII. p. 465. 1855.'] was the first to note that the limit depended upon the strength of stimulus and utilised the method as a means of measuring luminosity.' (396)

-

Cites

L. Bellarminow 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Ophthalmologie 35 (1) (1889), pp. 25-49.

L. Bellarminow 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Ophthalmologie 35 (1) (1889), pp. 25-49.

Description:'If a large disc be rotated and observations be made through two apertures of diameters proportionate to their distances from the centre, flicker appears and disappears at the same speed with the same luminosity at both apertures. This is only the case when the apertures are small so that their images fall entirely within the macula since the sensibility to intermittent stimuli of that part differs from the rest as shown by Exner [note: 'Pflüger's Archiv III. p. 237. 1870.'] and Bellarminow [note: Archiv f. Opthalmologie XXXV. p. 25. 1889.'].' (402)

-

Cites

O.N. Rood, 'On a Photometric Method which is Independent of Color', American Journal of Science 46 (3) (1893), pp. 173-176.

O.N. Rood, 'On a Photometric Method which is Independent of Color', American Journal of Science 46 (3) (1893), pp. 173-176.

Description:'it is due to Rood showing that fusion of stimuli depended upon frequency and luminosity of colour, that flicker photometry has developed.' (396)

-

Cites

S. Exner, 'Bemerkungen über intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 3 (1870), pp. 214-240.

S. Exner, 'Bemerkungen über intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 3 (1870), pp. 214-240.

Description:'If a large disc be rotated and observations be made through two apertures of diameters proportionate to their distances from the centre, flicker appears and disappears at the same speed with the same luminosity at both apertures. This is only the case when the apertures are small so that their images fall entirely within the macula since the sensibility to intermittent stimuli of that part differs from the rest as shown by Exner [note: 'Pflüger's Archiv III. p. 237. 1870.'] and Bellarminow [note: Archiv f. Opthalmologie XXXV. p. 25. 1889.'].' (402)

-

Cites

W. Filehne, 'Ueber den Entstehungsort des Lichtstaubes, der Starrblindheit und der Nachbilder', Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Ophthalmologie 31 (2) (1885), pp. 1-30.

W. Filehne, 'Ueber den Entstehungsort des Lichtstaubes, der Starrblindheit und der Nachbilder', Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Ophthalmologie 31 (2) (1885), pp. 1-30.

Description:'That the maximum speed at which the sensation of flicker is produced depended upon other factors besides luminosity was noted by Filehne [note: v. Graefe's Archiv XXXI. p. 20. 1885.'], whose observations were made on white discs on some of which only four black sectors of 45º each were painted. Rotated at a speed to produce 25-30 alternations per second, fusion occurred, while if the number of painted sectors were great, flicker might exist at a frequency of 74 alternations per second.' (396)

-

Cited by

O.F.F. Grünbaum, 'On Intermittent Stimulation of the Retina (Part II)', Journal of Physiology 22 (6) (1898), pp. 433-450

O.F.F. Grünbaum, 'On Intermittent Stimulation of the Retina (Part II)', Journal of Physiology 22 (6) (1898), pp. 433-450

Description:'Towards the end of Part I. [note: 'This Journal, XXI. p. 396. 1897'], a somewhat unexpected result of observations with intense stimuli was stated; in Section I. of this paper the experiments upon which that result was based will be given.' (433)

'The apparatus used for the above work lent itself excellently for repetition of the experiments published in Pt. I., for if the fine flicker seen were due to any other cause than intermittent illumination of the field, such as vibration etc., or was a purely subjective phenomenon [note: 'Burch. Proc. Physiol. Soc. p. xxxvi. 1897. (This Journal, XXI.)'] the half of the field illuminated continuously should have presented a similar appearance when its intensity was equal to the other half. This was not found to be the case and the results confirmed those already published.' (443)

'Some months [note: 'This Jourmal, xxi. p. 396. 1897.'] ago the effect of simultaneous contrast upon the frequency of alternation necessary to fuse moderate stimuli was investigated by me, the method adopted consisted in altering the ratio of the time that the eye was exposed completely to light or darkness and the transition period.

In that paper two kinds of flicker were distinguished, which more recently Schenk [note: ;Pflüger's Archiv, LXVIII. p. 32. 1897.'] has recognised and termed "Flackern" and "Flimmern," corresponding to ordinary or "coarse flicker " and "fine flicker" or molecular movement respectively.' (449)

-

Cited by

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

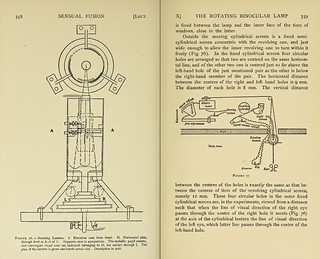

Description:'Sherrington was not the only British physiologist to experiment with illusions of temporal continuity at this time. Shortly after Sherrington's initial flicker study came out, his Cambridge compatriot Otto Fritz Frankeau Grünbaum published a two-part paper in the Journal of Physiology (Grünbaum 1897-1898). This study, which also addressed the rate at which alternating stimuli fused into continuous perception, strove for far greater precision than had Sherrington. Rather than direct both eyes to an external stimulus in the shape of a rotating disc, Grünbaum created a mechanism (fig. 3) that could project two separate beams of light onto the retina of a single eye. One of these beams was constant, thus constituting a point of comparison. The other however was interrupted by a disc with angular segments cut out of it. By rotating this disc at different speeds, Grünbaum sought to arrive at a more accurate estimation of the rates of exposure necessary for the experiences of different brightnesses. The parallels between the establishment of illusion-generating devices within physiology laboratories and that of cinematographic technology more generally are prominent here. One of the key elements of the cinematograph - and one of the most difficult pieces to co-ordinate with the movement of celluloid film-strips - was a disc or 'shutter' (similar to the ones Talbot and von Stampfer had developed) that cut off the projection of light at intervals proportional to the replacement of images on the projector. The minimal rate at which cinematographic images had to be replaced and exposed to view was determined by the rate at which images could be perceived as individual, rather than a continuous moving picture - i.e. by the phenomena of persistence of vision. [note: Münsterberg made the connection explicit. See Münsterberg 1916, 57-71.'] During the 1890s, the physiological study of flicker fusion and the construction of cinematographic devices went hand in hand.'

-

Cites

A. Fick, 'Ueber den zeitlichen Verlauf der Erregung in der Netzhaut', Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin (1863), pp. 739-764.

A. Fick, 'Ueber den zeitlichen Verlauf der Erregung in der Netzhaut', Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin (1863), pp. 739-764.

Description:'Fick found that under certain conditions 170 alternations might be necessary to produce fusion; this was the case when parallel lines were drawn on a drum which was rotated around an axis parallel to the lines: if, however, the observations were made through a slit no flicker was seen above 40 per second.

...

Fick suggested that movement of the eyes might be the explanation of the observations; wheni the speed of translation was small the eyes followed the sectors and thus flicker was not destroyed until high speeds were attained; the use of a window partially prevented this.' (396)