- External URL

- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): Otto Fritz Frankeau LeytonDate: 1898

- Current Holder(s)

-

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cites

A. Fick, 'Ueber den zeitlichen Verlauf der Erregung in der Netzhaut', Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin (1863), pp. 739-764.

A. Fick, 'Ueber den zeitlichen Verlauf der Erregung in der Netzhaut', Archiv für Anatomie, Physiologie und wissenschaftliche Medicin (1863), pp. 739-764.

Description:'The absolute accuracy of the Talbot-Plateau law was questioned by Fick [note: 'Reichert's Archiv, p. 739. 1863.'] in 1863, who adopted the same method of investigation as Plateau [note: 'Pogg. Annalen, XXXV. p. 457. 1835.'] had devised some years earlier.' (438)

'Fick [note: 'loc. cit.'] found that the luminosities of the rotating disc measured in this manner did not agree absolutely with that determined by the angle of black upon the disc.

[includes table of data from Fick]

All except the last disc were found to produce a sensation of greater luminosity than would have been expected from calculation of their angular brightness.' (439)

-

Cites

Artificial pupil/iris

Artificial pupil/iris

Description:'The method I adopted consisted in equalising the apparent luminosity of the two halves of a field, one of which was illuminated intermittently and the other continuously... The size of the field was regulated by an iris diaphragm; an artificial pupil (P) insured the correct position of the observer's eye.' (439-440)

-

Cites

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Reciprocal Action in the Retina as studied by means of some Rotating Discs', Journal of Physiology 21 (1) (1897), pp. 33-54.

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Reciprocal Action in the Retina as studied by means of some Rotating Discs', Journal of Physiology 21 (1) (1897), pp. 33-54.

Description:'Schenk [note: 'Pflüger's Archiv, LXVIII. p. 32. 1897.'] has recognised and termed "Flackern" and "Flimmern," corresponding to ordinary or "coarse flicker " and "fine flicker" or molecular movement respectively.' This experimenter has made observations on discs similar to those designed by Sherrington [note: 'This Journal, xxi. p. 37. 1897.'] to show areal induction, and concludes that if the ring-bands be observed separately and closely, disappearance of fine flicker occurs in both at the same speed of rotation. Bearing this in mind I have repeated observations upon the original discs and can but confirm Sherrington's results: that if the physiological difference of two visual stimuli be increased by simultaneous contrast, a greater frequency of alternation is required to produce their fusion, that if the physiological difference of the same too physical stimuli be decreased by the same method. By fusion I mean disappearance not only of coarse flicker but fine flicker as well.

It must be noted that if the ring-bands be examined separately and the eye be placed very close, little if any of the background will be seen, and thus the effect of simultaneous contrast may be greatly diiminished or even absolutely eliminated.' (449-450)

-

Cites

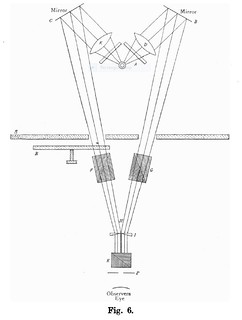

Device for detecting the point of perceptual equalization of an intermittent and a continuous source of illumination.

Device for detecting the point of perceptual equalization of an intermittent and a continuous source of illumination.

Description:'The observations given in the earlier part of this paper led me to believe that the [Talbot-Plateau] law would prove inaccurate when dealing with intense stimuli, and seemed to me worth investigation.

The method I adopted consisted in equalising the apparent luminosity of the two halves of a field, one of which was illuminated intermittently and the other continuously.

The luminosity of each half was easily adjusted, and the average physical value determinable by an apparatus, an explanation of which is most easily accomplished by reference to a diagram.

The source of light was an arc lamp (A), two mirrors (B) and (C) reflect pencils converging, towards (H), these pencils pass through lenses (E) and (D) to converge the rays, and then through polarisers (F) and (G) in order that their intensities can be regulated by analyser (K), after they have been deflected into parallelism by prisms (I), between the lamp and mirrors, sheets of ground-glass were intercepted. The size of the field was regulated by an iris diaphragm; an artificial pupil (P) insured the correct position of the observer's eye. The faces of the analyser (K) were parallel and normal to its axis of rotation: this prevented unequal reflection on its rotation.

The experiments were conducted as follows:

The analyser was placed in a definite position ɸ°, and one polariser F was turned into a position of total extinction, the analyser was then tulmed to ɸ + 90' and a black disc (R) from which a definite number of sectors of known angles had been removed was rotated between C and F.

Polariser G was turned until the halves of the field were approximately equal. After removal of the disc, the axis of G was determined by rotating the analyser to θ° where extinction occurred.

Now on turning the analyser to [(ɸ°+θ°)/2]... the two halves of the field were found to be equally illuminated when the apparatus was set up symmetrically: if this were not the case, the necessary alteration in position of lenses or mirrors was made.

The rotating disc (R) was then replaced, and the analyser turned until equality of the two halves was attained. Practice was found necessary to distinguish small differences in luminosity.

By careful arrangement of screens (S) and unstinted use of black paint, the half of the field which was intermittently illuminated appeared quite black when a sector of the disc was cutting off direct light from it: by contrast with the lighted half naturally the depth of the black appeared great, but even if a certain amount were reflected from the disc, it is fair to suppose that a certain definite fraction would be reflected, in which case, comparative results would not be vitiated in the slightest.

The usual methods of eliminating experimental errors were adopted, such as changing the polarisers, working at various parts of the scale, etc.

The most striking results were obtained by the substitution of an incandescent lamp for the arc, care being taken that the position was identical and that the plane of the filament of the lamp was perpendicular to the face of the analyser.' (439-441)

-

Cites

F. Schenck, 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Pflügers Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 68 (1-2) (1897), pp. 32-54

F. Schenck, 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Pflügers Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 68 (1-2) (1897), pp. 32-54

Description:'Some months [note: 'This Jourmal, xxi. p. 396. 1897.'] ago the effect of simultaneous contrast upon the frequency of alternation necessary to fuse moderate stimuli was investigated by me, the method adopted consisted in altering the ratio of the time that the eye was exposed completely to light or darkness and the transition period.

In that paper two kinds of flicker were distinguished, which more recently Schenk [note: Pflüger's Archiv, LXVIII. p. 32. 1897.'] has recognised and termed "Flackern" and "Flimmern," corresponding to ordinary or "coarse flicker " and "fine flicker" or molecular movement respectively.' (449)

-

Cites

J. Plateau, 'Betrachtungen über ein von Hrn Talbot vorgeschlagenes photometrisches Princip', Poggendorff's Annalen der Physik 111 (7) (1835), pp. 457-468.

J. Plateau, 'Betrachtungen über ein von Hrn Talbot vorgeschlagenes photometrisches Princip', Poggendorff's Annalen der Physik 111 (7) (1835), pp. 457-468.

Description:'The absolute accuracy of the Talbot-Plateau law was questioned by Fick [note: 'Reichert's Archiv, p. 739. 1863.'] in 1863, who adopted the same method of investigation as Plateau [note: 'Pogg. Annalen, XXXV. p. 457. 1835.'] had devised some years earlier.' (438)

-

Cites

J.B. Haycraft, 'Luminosity and Photometry', Journal of Physiology 21 (2-3) (1897), pp. 126-146.

J.B. Haycraft, 'Luminosity and Photometry', Journal of Physiology 21 (2-3) (1897), pp. 126-146.

Description:'On increasing the intensity of intermittent stimuli a rapid increase in frequency is necessary at first to produce fusion; after a certain frequency has been attained a further increase in intensity does not necessitate a further increase in frequency, this has been shown by Bellarminow [note: 'Archiv f. Ophthalmolgie, XXV. p. 25. 1889.'] and surmised by Haycraft [note: 'This Journal, XXI. p. 139. 1897.']: but on still further increasing the intensity of the stimuli fusion occurs with a decreased frequency.' (435)

-

Cites

K. Marbe, 'Theorie des Talbot'schen Gesetzes', Philosophische Studien 12 (1896), pp. 279-296.

K. Marbe, 'Theorie des Talbot'schen Gesetzes', Philosophische Studien 12 (1896), pp. 279-296.

Description:'Marbe [note: 'Wundt Philosoph. Stud. XII. p. 279. 1896 and IX. p. 384. 1893.'] has stated several theoretical reasons for considering the Talbot-Plateau law inaccurate but has not made any direct observations.' (439)

-

Cites

![K. Marbe, '[title unknown]' Philosophische Studien 8 (1893), pp. 615-637.](/cslide/img/icons/document.png) K. Marbe, '[title unknown]' Philosophische Studien 8 (1893), pp. 615-637.

K. Marbe, '[title unknown]' Philosophische Studien 8 (1893), pp. 615-637.

Description:'Marbe [note: 'Wundt Philosoph. Stud. XII. p. 279. 1896 and IX. p. 384. 1893.'] has stated several theoretical reasons for considering the Talbot-Plateau law inaccurate but has not made any direct observations.' (439)

-

Cites

L. Bellarminow 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Ophthalmologie 35 (1) (1889), pp. 25-49.

L. Bellarminow 'Ueber intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Ophthalmologie 35 (1) (1889), pp. 25-49.

Description:'On increasing the intensity of intermittent stimuli a rapid increase in frequency is necessary at first to produce fusion; after a certain frequency has been attained a further increase in intensity does not necessitate a further increase in frequency, this has been shown by Bellarminow [note: 'Archiv f. Ophthalmolgie, XXV. p. 25. 1889.'] and surmised by Haycraft [note: 'This Journal, XXI. p. 139. 1897.']: but on still further increasing the intensity of the stimuli fusion occurs with a decreased frequency.' (435)

-

Cites

L. Hermann, Handbuch der Physiologie (Leipzig, 1879).

L. Hermann, Handbuch der Physiologie (Leipzig, 1879).

Description:'Two main theories have been suggested to explain the fact that intermittent retinal stimuli repeated above a certain frequency give rise to a steady sensation.

The older, which I shall in future style the "persistence theory," seems to have been suggested by d'Arcy

'Two main theories have been suggested to explain the fact that intermittent retinal stimuli repeated above a certain frequency give rise to a steady sensation.

The older, which I shall in future style the "persistence theory," seems to have been suggested by d'Arcy [note: 'Mem. Akd. Sci. p. 439. 1765.'] in 1765 and maintains that a steady sensation results from intermittent stimuli, when the intervening periods do not exceed the time of duration of the positive after-image of undiminished brightness: in fact, attempts were made by this observer to determine this quantity by noting the minimum freouency with which a burning coal must be rotated in order to produce a sensation of a ring of fire: 0.133 secs. was his estimation.

All subsequent writers, Plateau, Talbot, Helmholtz, etc. adopt d'Arcy's view, Fick [note: Hernann's Handbuch, III. p. 215. 1879.'] being the first to suggest an alternative. This author accepted Exner's [note: Sitzungsberichte Akad. Wein. LVIII. p. 601. 1868, and Pflüger's Archiv, III. p. 240. 1870.'] conclusion, that if the eye be exposed to black after having been stimulated by light, there is at first a rapid fall in the brightiness of the positive after-image, which then more gradually disappears; the curve representing the decrease and disappearance being of exactly a similar nature to that representing the growth of sensation produced by a white stimulus.

Fick diagrammatically represented the sensation resulting from intermittent stimulus by a serrated line, the abscissa being the timerelation and the ordinates the strength of sensation, and pointed out that if the frequency become great, the amplitude of oscillation of sensation diminishes until a frequency is reached at which a continuous smooth sensation results.

It is surprising that writers after Fick's explanation did not adopt his view, since even if Exner's statement that under normal conditions the duration of the after-image of undiminished brightness is infinitely short, be disallowed, nevertheless the persistence-theory seems unsatisfactory' (443-444)

-

Cites

O.F.F. Grünbaum, 'On Intermittent Stimulation of the Retina (Part I)', Journal of Physiology 21 (4-5) (1897), pp. 396-402.

O.F.F. Grünbaum, 'On Intermittent Stimulation of the Retina (Part I)', Journal of Physiology 21 (4-5) (1897), pp. 396-402.

Description:'Towards the end of Part I. [note: 'This Journal, XXI. p. 396. 1897'], a somewhat unexpected result of observations with intense stimuli was stated; in Section I. of this paper the experiments upon which that result was based will be given.' (433)

'The apparatus used for the above work lent itself excellently for repetition of the experiments published in Pt. I., for if the fine flicker seen were due to any other cause than intermittent illumination of the field, such as vibration etc., or was a purely subjective phenomenon [note: 'Burch. Proc. Physiol. Soc. p. xxxvi. 1897. (This Journal, XXI.)'] the half of the field illuminated continuously should have presented a similar appearance when its intensity was equal to the other half. This was not found to be the case and the results confirmed those already published.' (443)

'Some months [note: 'This Jourmal, xxi. p. 396. 1897.'] ago the effect of simultaneous contrast upon the frequency of alternation necessary to fuse moderate stimuli was investigated by me, the method adopted consisted in altering the ratio of the time that the eye was exposed completely to light or darkness and the transition period.

In that paper two kinds of flicker were distinguished, which more recently Schenk [note: ;Pflüger's Archiv, LXVIII. p. 32. 1897.'] has recognised and termed "Flackern" and "Flimmern," corresponding to ordinary or "coarse flicker " and "fine flicker" or molecular movement respectively.' (449)

-

Cites

P. d'Arcy, 'Mémoire sur la durée de la sensation de la vue', Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris (1765), pp. 439-451.

P. d'Arcy, 'Mémoire sur la durée de la sensation de la vue', Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris (1765), pp. 439-451.

Description:'Two main theories have been suggested to explain the fact that intermittent retinal stimuli repeated above a certain frequency give rise to a steady sensation.

The older, which I shall in future style the "persistence theory," seems to have been suggested by d'Arcy [note: 'Mem. Akd. Sci. p. 439. 1765.'] in 1765 and maintains that a steady sensation results from intermittent stimuli, when the intervening periods do not exceed the time of duration of the positive after-image of undiminished brightness: in fact, attempts were made by this observer to determine this quantity by noting the minimum freouency with which a burning coal must be rotated in order to produce a sensation of a ring of fire: 0.133 secs. was his estimation.

All subsequent writers, Plateau, Talbot, Helmholtz, etc. adopt d'Arcy's view, Fick [note: Hernann's Handbuch, III. p. 215. 1879.'] being the first to suggest an alternative.' (443-444)

-

Cites

William Halse Rivers Rivers

William Halse Rivers Rivers

Description:'Dr Rivers was good enough to make somne number of observations for me, but as the experiments seemed to tire his eyes rapidly, only parts of series are recorded, and those happen to be with different units of intensity of light.' (436-437)

-

Cites

S. Exner, 'Bemerkungen über intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 3 (1870), pp. 214-240.

S. Exner, 'Bemerkungen über intermittirende Netzhautreizung', Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 3 (1870), pp. 214-240.

Description:'Two main theories have been suggested to explain the fact that intermittent retinal stimuli repeated above a certain frequency give rise to a steady sensation.

The older, which I shall in future style the "persistence theory," seems to have been suggested by d'Arcy

'Two main theories have been suggested to explain the fact that intermittent retinal stimuli repeated above a certain frequency give rise to a steady sensation.

The older, which I shall in future style the "persistence theory," seems to have been suggested by d'Arcy [note: 'Mem. Akd. Sci. p. 439. 1765.'] in 1765 and maintains that a steady sensation results from intermittent stimuli, when the intervening periods do not exceed the time of duration of the positive after-image of undiminished brightness: in fact, attempts were made by this observer to determine this quantity by noting the minimum freouency with which a burning coal must be rotated in order to produce a sensation of a ring of fire: 0.133 secs. was his estimation.

All subsequent writers, Plateau, Talbot, Helmholtz, etc. adopt d'Arcy's view, Fick [note: Hernann's Handbuch, III. p. 215. 1879.'] being the first to suggest an alternative. This author accepted Exner's [note: Sitzungsberichte Akad. Wein. LVIII. p. 601. 1868, and Pflüger's Archiv, III. p. 240. 1870.'] conclusion, that if the eye be exposed to black after having been stimulated by light, there is at first a rapid fall in the brightiness of the positive after-image, which then more gradually disappears; the curve representing the decrease and disappearance being of exactly a similar nature to that representing the growth of sensation produced by a white stimulus.

Fick diagrammatically represented the sensation resulting from intermittent stimulus by a serrated line, the abscissa being the timerelation and the ordinates the strength of sensation, and pointed out that if the frequency become great, the amplitude of oscillation of sensation diminishes until a frequency is reached at which a continuous smooth sensation results.

It is surprising that writers after Fick's explanation did not adopt his view, since even if Exner's statement that under normal conditions the duration of the after-image of undiminished brightness is infinitely short, be disallowed, nevertheless the persistence-theory seems unsatisfactory' (443-444)

in 1765 and maintains that a steady sensation results from intermittent stimuli, when the intervening periods do not exceed the time of duration of the positive after-image of undiminished brightness: in fact, attempts were made by this observer to determine this quantity by noting the minimum freouency with which a burning coal must be rotated in order to produce a sensation of a ring of fire: 0.133 secs. was his estimation.

All subsequent writers, Plateau, Talbot, Helmholtz, etc. adopt d'Arcy's view, Fick [note: Hernann's Handbuch, III. p. 215. 1879.'] being the first to suggest an alternative. This author accepted Exner's [note: Sitzungsberichte Akad. Wein. LVIII. p. 601. 1868, and Pflüger's Archiv, III. p. 240. 1870.'] conclusion, that if the eye be exposed to black after having been stimulated by light, there is at first a rapid fall in the brightiness of the positive after-image, which then more gradually disappears; the curve representing the decrease and disappearance being of exactly a similar nature to that representing the growth of sensation produced by a white stimulus.

Fick diagrammatically represented the sensation resulting from intermittent stimulus by a serrated line, the abscissa being the timerelation and the ordinates the strength of sensation, and pointed out that if the frequency become great, the amplitude of oscillation of sensation diminishes until a frequency is reached at which a continuous smooth sensation results.

It is surprising that writers after Fick's explanation did not adopt his view, since even if Exner's statement that under normal conditions the duration of the after-image of undiminished brightness is infinitely short, be disallowed, nevertheless the persistence-theory seems unsatisfactory' (443-444)

-

Cites

S. Exner, 'Ueber die zu einer Gesichtswahrnehmung nöthige Zeit', Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe, 58 (2) (1868), pp. 601-632.

S. Exner, 'Ueber die zu einer Gesichtswahrnehmung nöthige Zeit', Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften: Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Classe, 58 (2) (1868), pp. 601-632.

Description:'Two main theories have been suggested to explain the fact that intermittent retinal stimuli repeated above a certain frequency give rise to a steady sensation.

The older, which I shall in future style the "persistence theory," seems to have been suggested by d'Arcy [note: 'Mem. Akd. Sci. p. 439. 1765.'] in 1765 and maintains that a steady sensation results from intermittent stimuli, when the intervening periods do not exceed the time of duration of the positive after-image of undiminished brightness: in fact, attempts were made by this observer to determine this quantity by noting the minimum freouency with which a burning coal must be rotated in order to produce a sensation of a ring of fire: 0.133 secs. was his estimation.

All subsequent writers, Plateau, Talbot, Helmholtz, etc. adopt d'Arcy's view, Fick [note: Hernann's Handbuch, III. p. 215. 1879.'] being the first to suggest an alternative. This author accepted Exner's [note: Sitzungsberichte Akad. Wein. LVIII. p. 601. 1868, and Pflüger's Archiv, III. p. 240. 1870.'] conclusion, that if the eye be exposed to black after having been stimulated by light, there is at first a rapid fall in the brightiness of the positive after-image, which then more gradually disappears; the curve representing the decrease and disappearance being of exactly a similar nature to that representing the growth of sensation produced by a white stimulus.

Fick diagrammatically represented the sensation resulting from intermittent stimulus by a serrated line, the abscissa being the timerelation and the ordinates the strength of sensation, and pointed out that if the frequency become great, the amplitude of oscillation of sensation diminishes until a frequency is reached at which a continuous smooth sensation results.

It is surprising that writers after Fick's explanation did not adopt his view, since even if Exner's statement that under normal conditions the duration of the after-image of undiminished brightness is infinitely short, be disallowed, nevertheless the persistence-theory seems unsatisfactory' (443-444)

-

Cited by

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

T. Quick, 'Disciplining Physiological Psychology: Cinematographs as Epistemic Devices, 1897-1922', Science in Context 30 (4), pp. 423-474.

Description:'Nor was Sherrington the only British physiologist to experiment with illusions of temporal continuity at this time. Shortly after Sherrington's initial flicker study came out, his Cambridge compatriot Otto Fritz Frankeau Grünbaum published two papers in the Journal of Physiology. [note: 'O.F.F. Grünbaum, 'On Intermittent Stimulation of the Retina (Parts I. and II.)', Journal of Physiology 21 (4-5) (1897), pp. 396-402 and 22 (6) (1898), pp. 433-450.'] These studies, which also addressed the rate at which alternating stimuli fused into continuous perception, strove for far greater precision than had Sherrington. Rather than direct both eyes to an external stimulus in the shape of a rotating disc, Grünbaum created a mechanism (fig. 3) that could project two separate beams of light onto the retina of a single eye. One of these beams was constant, thus constituting a point of comparison. The other beam however was interrupted by a rotating disc with angular segments cut out of it. By rotating this disc at different speeds, Grünbaum sought to arrive at a more accurate estimation of the rates of exposure necessary for the experiences of different brightnesses. The parallels between the establishment of illusion-generating devices within physiology laboratories and that of cinematographic technology more generally are prominent here. One of the key elements of the cinematograph - and one of the most difficult pieces to co-ordinate with the movement of celluloid film-strips - was a disc or 'shutter' (similar to the ones Talbot and von Stampfer had developed) that cut off the projection of light at intervals proportional to the replacement of images on the projector. The minimal rate at which cinematographic images had to be replaced and exposed to view was determined by the rate at which images could be perceived as individual, rather than a continuous moving picture - i.e. by the phenomena of persistence of vision. [note: 'Münsterberg made the connection explicit. See H. Münsterberg, The Photoplay: a Psychological Study (New York and London: D. Appleton, 1916), pp. 57-71.'] During the 1890s, the physiological study of flicker fusion and the construction of cinematographic devices went hand in hand.'

-

Quotes

A. Charpentier, 'Influence de l'Intensitie Lumineuse sur la Persistance des Impressions Rétiniennes', Comptes rendus des séances de la Société de biologie et de ses filiales 8 (4) (1887), pp. 89-92.

A. Charpentier, 'Influence de l'Intensitie Lumineuse sur la Persistance des Impressions Rétiniennes', Comptes rendus des séances de la Société de biologie et de ses filiales 8 (4) (1887), pp. 89-92.

Description:'it was on the above theory [of 'persistance' relating to the phenomena of loss of flicker sensation] that Charpentier [note: 'Compt. Rendus Soc. Biolog. Series VIII. Tom. IV. 1887. (Several papers.)'] in 1887 drew the conclusion from observation on intermittent retinal stimulation that "the persistence of the impressions of luminosity decreases when the light increases and vice versa."

Contrast the statement with that of Helmholtz [note: 'Phys. Optik. p. 503. 1896.'], "the greater intensity of the primary light the greater is the brightness of the positive after-image and the longer does it last."

If curves were plotted to represent the relation of intensity of primary light to the duration of after-image, the intensity being the abscissa and duration the ordinates, upon Helmholtz's view the curve would start from the zero point and gradually rise, the exact nature is not known as direct determination of length of after-image offers insuperable difficulties: according to Charpentier with very small luminosity we should have an after-image of long duration which would gradually decrease as the luminosity increased, in fact the one curve would be the mirror image of the other.' (445)

-

Quotes

O.N. Rood, 'On a Photometric Method which is Independent of Color', American Journal of Science 46 (3) (1893), pp. 173-176.

O.N. Rood, 'On a Photometric Method which is Independent of Color', American Journal of Science 46 (3) (1893), pp. 173-176.

Description:'the scheme [outline above] satisfies Rood's [note: American Journ. of Science, XLVI. p. 173. 1893.'] conclusion: "the sensation called flickering is independent of wave-length and is connected with change of luminosity". (446)