- External URL

- Creation

-

Creator (Definite): William McDougallDate: 1901

- Current Holder(s)

-

NB - links to second and third parts: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mind/X.1.210 and http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mind/X.1.347

- No links match your filters. Clear Filters

-

Cites

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Reciprocal Action in the Retina as studied by means of some Rotating Discs', Journal of Physiology 21 (1) (1897), pp. 33-54.

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Reciprocal Action in the Retina as studied by means of some Rotating Discs', Journal of Physiology 21 (1) (1897), pp. 33-54.

Description:'There is [sic] then a very large number of striking phenomena of fundamental importance that cannot be recounted for by the theory of 'Gegenfarben,' [as advocated by Hering and G.E. Müller] and many of them are absolutely irreconcilable with any form of that theory.

Young's theory, on the other hand, if we incorporate with it the hypothesis of the separate W-exciting apparatus having its retinal seat in the rods, as urged by v. Kries, Rollet's theory of contrast and the theories of induction and after-images set forth above, explains fully all the phenomena described above; and, with the exception of certain observations of a complex character, very difficult to interpret, such as Muller's experiments on galvanic stimulation of the eyes and some of Prof. Sherrington's flicker experiments, I cannot discover any important fact connected with light- and colour-vision with which it is incompatible or that it fails to illumine.' (382)

-

Cites

Portable dark chamber

Portable dark chamber

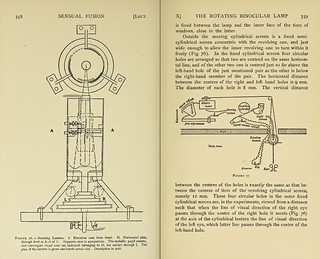

Description:[note on pp. 355-356]: A piece of apparatus, which may he called a portable dark chamber, is very useful in the study of after-images. It consists of the following parts: a piece of 1 inch plank, 18 inches in width, and 2 feet 6 inches in stands vertically upon this plank, its lower edge is let into a slot running along the middle of it, and it is held firmly in position by angle-pieces. A little above its centre, the square board has a circular hole, 3 ½ inches in diameter. At the top comers of the board a pair of light wooden rods are attached by hinges and can be fixed so as to project horizontally from it, parallel to one another, and at right angles to the plane of the board. Two pieces of black cloth, the inner one of black velvet, the outer of black linen, each about 3 ½ yards in length, are tacked by one edge to the top and sides of the square board and spread over the horizontal rods. A strip of cloth about 1 yard wide tacked by one edge to the base-board and a back-flap of black velvet complete the walls of the chamber. The base-board being placed upon a table at one edge the observer sits within the curtains with his eyes at the level of the hole in the vertical board, and by sitting upon the free ends of the curtains can completely exclude all light. On the inner surface of the vertical board, above and below the circular hole, are two pairs of projecting ledges to hold the photographic shutter and the glass plates. Where no dark room is available this simple piece of apparatus can be made to serve many of the purposes of one. It can also be used as a ' Dunkel-Tonne,' and even where a dark room is available this dark chamber presents the advantage that it can be placed so as to receive the direct rays of the sun through the hole in the vertical board. I have made a second example with two apertures about 9 inches apart in place of the one, each being filled with shutter and glass-plates. This is in many ways a great improvement. I find the Thornton-Pickard shutter for time and instantaneous exposures, well suited for use in such a chamber.' (355-356)

-

Cited by

C. Sherrington, 'Observations on 'flicker' in binocular vision', Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 71 (1902), pp. 71-76.

C. Sherrington, 'Observations on 'flicker' in binocular vision', Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 71 (1902), pp. 71-76.

Description:'Interesting experimental difficulties... were occassioned by the reciprocal and often antagonistic influences exerted by one retina upon another in ways studied and described recently by Dr. W. McDougall.' (75)

-

Cited by

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Binocular Flicker and the Correlations of Activity of 'Corresponding' Retinal Points', Journal of Psychology 1 (1) (1904), pp. 26-60.

C.S. Sherrington, 'On Binocular Flicker and the Correlations of Activity of 'Corresponding' Retinal Points', Journal of Psychology 1 (1) (1904), pp. 26-60.

Description:'Experiment 8. Two images LR and λp½ were placed in the visual field for mutual comparison. LR was composed of left-eye and right-eye equal and corresponding disc-shaped images as in previous experiments. λp½ was composed of a left-eye image similar to L and R except that it lay just above or below them in the visual field. With λ's right half was combined the image of the right half of a lantern image similar again to the others, except that its left half was screened absolutely off into the blank undetailed darkness of the general field. When this was done the two opposite visual images LR and λp½ regarded under perfectly steady ocular fixation, were stable, and no difference of brightness was discernible between them. Moreover no join was seen between the halves of λp½ and no difference of brightness between the halves. After prolonged inspection of them rivalry became troublesome; but a judgment could be clearly arrived at before that happened.

In this experiment it might possibly be that equality of brightness between the halves of λp½ was due to image p½ not really being in consciousness at all during the comparison. The image might possibly lapse under competition with the partly dissimilar correspondingly placed left-eye image λ. Some of the experiments carried out by McDougall [note: 'Mind, 1901, N.S. x. p. 63 .'] give validity to such possible objection. The perceptibility of the horizontal bar in the right half of the image λp½ was guarantee however that at least part of the uniocular image p½ was present. But to ascertain more surely whether image p½ was really during the visual equation co-operating in consciousness with λ the following further arrangement was employed.

[Diagram 11: image showing altered exposure patterns of LR and λp½]

Experiment 9, (Diagram 11). With the revolving lantern so arranged that images L, R, λ and p½ were all of equal brightness when steady and unflickering, p½ was given a lesser frequency of intermission, so as to flicker while the others did not. A speed of revolution of lantern was then used at which just a trace of flicker was perceptible in p½ when binocularly combined with λ. The equation LR—λp½ was then found to hold while flicker was still just traceable in the right half of λp½. There was then no join seen hetween the halves of λp½ nor any difference between the brightness of the halves. So long as ocular fixation was steady no rivalry disturbed the observation.

In this case there could, I venture to think, be no question but that the one half of λp½ was truly binocular, for the trace of flicker was perceptible during the actual performance of the comparison. Yet no difference of brightness was perceived between LR and λp½, and the two Literal halves of compared together were of like brightness.' (48-49)

'McDougall' [note: '"The Principle underlying Fechner's 'Paradoxical Experiment' and the Predominance of Contours in the struggle of two Visual Fields." This Journ. p. 114.'], in applying to 'retinal rivalry' and 'prevalence of contours' his principle of competition of inter-related nerve-elements for energy, also argues a "separateness of the visual cortical areas for the two eyes." He brings forward striking experiments in evidence of this. In one of these he [note: Mind, 1901, N.S. X. p. 56.'] shows that an after-image, left from excitation of one retina, is more strongly revived by subsequent weak diffuse excitation of that same retina than of its fellow. More recently, in experiments proving reinforcement of visual sensations by the activity of the ocular muscles, as evidenced by after-image observations, he [note: Mind, 1903, N.S. XII. p. 473.'] shows that activity of the intrinsic muscles of an eye sends up to the brain an influence, reinforcing the activity of the cerebro-retinal tract of that eye, while it exerts no such effect upon the corresponding tract of the other eye, or exerts it in a minor degree only.' (58)